Hyperfemininity is an exaggerated adherence to a feminine gender role as it relates to heterosexual relationships.

— Sarah K. Murnen & Donn Byrne (1991)

I love to start my articles with disclaimers, and this one will not be different. I’m not an expert in feminist theory, and not even qualified to be one. As such, naturally enough, I’m not up to date to the latest trends in feminist theory — I just have some very superficial understanding. And I’m also aware that the people from the queer theory have ‘joined forces’ with the feminists and tried to establish a common ground. All this, I’m afraid, is truly utterly beyond my knowledge. So be weary of what I’m saying: it’s quite certain that somewhere, on one of the gazillions books, articles, blogs, or forums, trillions of people might have emitted a contrary opinion to my own, substantiated it with very strong arguments, and settled the issue decades ago — while I’m totally ignorant about that discussion. So, being in the dark about the subject, I’m prone to make gross mistakes.

I love to start my articles with disclaimers, and this one will not be different. I’m not an expert in feminist theory, and not even qualified to be one. As such, naturally enough, I’m not up to date to the latest trends in feminist theory — I just have some very superficial understanding. And I’m also aware that the people from the queer theory have ‘joined forces’ with the feminists and tried to establish a common ground. All this, I’m afraid, is truly utterly beyond my knowledge. So be weary of what I’m saying: it’s quite certain that somewhere, on one of the gazillions books, articles, blogs, or forums, trillions of people might have emitted a contrary opinion to my own, substantiated it with very strong arguments, and settled the issue decades ago — while I’m totally ignorant about that discussion. So, being in the dark about the subject, I’m prone to make gross mistakes.

Then again, this is just my opinion on my own blog 🙂 and not an academic paper…

What’s hyperfemininity and why do feminists hate it?

Let’s start from the basics, and why I’m tackling this subject today. I believe that we can say that the feminist movement has, to a degree, triumphed: as I write these lines, a woman was finally nominated as a presidential candidate in the US. We Europeans might be used to having female leaders at all levels at least since the 1980s, but the Americans are far more conservative in that regard. Still, barriers have been overturned all over the world, and, paraphrasing Hillary Clinton, ‘women’s rights are human rights’ — something which is true all over the Western world, but that is slowly also becoming true in many (if not most) developing countries.

It would be unfair to say that the feminist movement has accomplished all goals, and therefore it can become extinct. Of course not. One thing is to claim victory over the laws — in the sense that discrimination against women becomes illegal — the other is to claim victory over society. Women, even in the most democratic countries, are still underrepresented in the workforce, especially on high-paying management levels. They are still forced to become ‘supermoms’ — taking care of the children while simultaneously holding a job, improving their education, and managing to keep the house clean. Single mothers still raise a few eyebrows (even if it’s not as bad as it was a few decades ago). So there is a long way to go.

But there is also the reverse side to contemplate: it’s not just bad news! For instance, in the Western world, education equals financial independence (you’re more likely to get a better-paying job), and therefore more women are getting higher education than men — and they are finishing their degrees quickly (while men are dropping out more and more). As I mentioned in a previous article, certain kinds of jobs, which were once held almost exclusively by men, now have women in the majority: typical examples include medical doctors, academic teachers, lawyers, judges, accountants. This is obviously a good sign, since those are high-paying jobs. There is much for women to celebrate — it’s been a very tough journey, but women are ‘getting there’.

Now, one of the fundamental ideological battles in feminism is the de-objectification of women (in general, not only as ‘sex toys’). This goes beyond merely overcoming stereotypes. As we can still see in many kinds of ads, women’s bodies are still used as pure objects to sell a product. Such ads might be more clever these days, more subtly done, etc. but they still treat women as objects. This will still take some time to change.

And the roles at home are still stuck to stereotypes. More and more men know how to cook (after all, the best chefs in the world are all men — and they aren’t necessarily gay!), but, once they get married, it’s usually the wife that handles all the chores. Men may ‘help’ at the home, but they just play a secondary role in the overall management. Women are still expected to do most of the chores, worry about most of the things, do most of the home shopping, and deal with the kids most of the time. They are ‘allowed’, or even ‘encouraged’, to get a job and additional education — so long as they keep up with all the chores they have to do at home. Supermoms indeed.

Therefore, the picture of the contemporary woman is the ‘overachiever’. She has to be much better than all men, and, on top of that, she still has to do all the typical ‘womanly work’ that is socially ‘expected’ from her. One might wonder if this image of the contemporary woman is so positive at all. Well, it shows that at least part of the prejudice against women is being eliminated, but there is a lot that is not; in other words, women are ‘allowed’ to do whatever men do (get a good education and a high-paying job, for example) so long as they still take care of all the ‘womanly work’ that they’re socially expected to do.

Okay. So this is the state-of-the-art of the accomplishments of the feminist movement so far. They can tap themselves on their collective shoulders and congratulate themselves on what has been done, but they are fully aware that there is quite a lot still to be done — it’s not yet time to take a break!

As we entered third wave feminism in the 1990s, a few changes were made in the overall ideology. One very crucial change was to accept that women would be allowed to define their own feminism, that is, grant the right to the individual (woman) to say what is right to her on an individual basis — even if it sometimes means pulling away from (mainstream) feminism. One aspect of third wave feminism has to do with visual self-image. Women in the previous wave were strongly encouraged, nay, even forced to a degree to abandon all traits that were deemed to be ‘feminine’, since by those very traits they were pushing along patriarchalism’s stereotypes and perpetuating them. I quite well remember in the 1980s when girls would dress like boys — short hair, no makeup or earrings, T-shirts and loose jeans, and tennis shoes or flat sandals were definitely unisex attire. Their whole attitude also changed to comply with their ‘new image’. While a few still favoured occasional touches of a more feminine visual — say, dying the hair (which was not as commonplace among males as it is today) or perhaps wear one earring or a (unisex-looking) bracelet — many were quite happy to be free from the usual clothing stereotypes that were ‘expected’ from them just a generation before.

In the 1990s, however, many women started to question this approach. They would like to have the freedom to look feminine — but do it for themselves, and not to please the patriarchy. This is a quite important and fundamental distinction: third wave feminism accepted that women were allowed to become feminine again so long as they did it only for themselves. This, naturally, created a difficulty: how could you tell that a woman was ‘dressing up’ just because she wanted to, and not because she wanted to impress a potential boyfriend? How narrow was the dividing line? This was also the time when so-called ‘lipstick lesbians’ (those who favoured a very feminine image and distanced themselves from the usual ‘butch’ look) were seen with suspicion (of possibly being bisexual and not ‘true lesbians’). And, of course, it marked the return of long hair, dresses, makeup, and high heels, to the chagrin of die-hard second wave feminists.

Still, many prominent third wave feminists did, indeed, claim for themselves the right to look pretty much as they wanted, even if their choice was to look, well, stereotypically feminine. This made many second wave feminists cringe, or even panic, in fear that all that they had fought for would come to a halt, if women would start to pick up old stereotypes again…

The truth is that third wave feminism — stripped as much of its ideology as possible (if at all possible!) — is mostly concerned about human rights, and not only about women rights (yes, Hillary spoke her famous words about that time, too). It was also a time where queer theory started to get read, and accepted, and even partially incorporated, into feminism as well — and vice-versa. Suddenly, transgender females became numerous enough that the question would be raised if they were part of the feminist movement or not. In other words: as individuality (the right to express yourself) was married to individual rights (like the right not to be discriminated based on gender, race, religion… but also based on what you wore!), inevitably this would mean that there would be many different co-existing opinions about what was morally/ethically correct for women to adopt (in the sense that feminism was attempting to destroy the patriarchal society’s stereotypes and create a society where women would truly have an equal place with men).

Of course, if you wanted to dress in a feminine way that was attractive to men, feminists had a problem with that. Either they had to accept the individual right of dressing as you wished, or they had to put some limits on what was acceptable or not (like second wave feminists did). This was a problem.

But hyperfemininity posed an even greater problem. Some groups of women (granted, probably not members of the inner core of the feminist movement…) claimed for themselves the right to conform to stereotypes. In other words, not only did they want to look visually appealing to men, but they wanted to live a submissive role in society where they, as women, would not need to work but just to raise children and do basic housekeeping.

Feminists, of course, saw that as a menace to the overall movement! After so many decades of fights, now they had to face some women who — claiming the right to their individual choice — were actively wanting to perpetuate the patriarchal stereotypes. Ouch. That was a low blow. What to do with those people?

In some cases they were talking to highly intelligent and educated women, who still claimed to be ‘feminists’, in the sense that the right to choose their lives was theirs, and only theirs. Nobody had forced them to go into a stereotypical female role; they chose it, of their own free will, according to the best tenets of feminist ideology. No male person pushed them into the role of submissive wife; they deliberately aimed for that role, and consciously did all what was expected of a stereotypical woman to achieve their goals. Ironically, hyperfeminine women — no matter what their intellect — not only attract men more easily (for sexual contacts), but they also seem to have an advantage in interpersonal relationships, even relatively neutral ones: men simply listen with more attention to women who look great.

These are goals that run contrary to the whole point of feminist ideology. But… the alternative was to prevent women from exercising their free will and their right to choice, and to constrain their freedom. What was more important — from an ideological point of view? The constraints imposed on women by second wave feminism were mostly the reason why it had been progressively abandoned — it got too much backlash.

So… in short, hyperfemininity poses a serious threat to feminist ideology, because it seems that giving women freedom to choose, a large part of them tend to chose falling back to stereotypes. This puts the whole point of the movement in question. And remember that third wave feminism today is mostly about human rights (all humans, not only those who have been assigned female at birth), even though many feminists disagree with that, or disagree with the scope of ‘feminism’ and who is included in it. And here is where transgender people pose another significant problem.

Hate fuels extremist feminism: TERF

One reason why LGB groups quickly adopted the T was that they learned to understand that transgender rights were also human rights — the same rights that the LGB crowd has been fighting for. Even though transgender issues are, to a degree, more complex than LGB issues, it was clear early on that both groups could join forces as allies. Naturally enough, feminist groups — also fighting for human rights, after all — seemed to be good allies as well, especially because so many feminist activists were also homosexual. There was supposed to be a natural affinity between them — intellectually, as queer theory merged with feminist theory; but also from the perspective of civil rights, justice, equal opportunities, and so forth. Both kinds were obviously fighting the same war, side by side, even if the actual targets were not exactly the same.

Enter radical feminism.

Radical feminists had an issue with the potential inclusion of transgender women in their sorority. Transgender women, of course, claim that they are women to the core — just had a ‘birth defect’ that made people believe they were male, but they had it corrected — and therefore wish to ‘fight the good fight’ as well. Radical feminists, by contrast, asked themselves if ‘trans women’ were not merely a plot by the leaders of the patriarchal society in order to undermine the feminist movement; this made a lot of influential feminists deny access to trans women, claiming that they were nothing less than ‘men in disguise’. As you can imagine, this couldn’t be more offensive to trans women — and rather shocking, when coming from a group fighting for human rights.

Feminist fights, however, are not exactly about ‘equality’ — depending on the group, of course — but often they claim that either gender ought to be abolished (a view that could be shared by many transgender activists as well) or, by contrary, that gender is definitely binary, but ‘males’ have a huge amount of privilege, and the strength to maintain that privilege, so they have to be fought until the end. Transgender people were just confusing the issue, asking strange questions like ‘what is a woman, what is a man?’. In fact, among TERF (Trans-Exclusive Radical Feminism) — the embodiment of anti-trangender hate inside the feminist activists — such questions did not need to be asked at all. Trans people were a nuisance. They put everything in question. The world was simple, black and white, and feminism was the ‘right’ side fighting a battle against the ‘wrong’ side. Questioning philosophically what exactly the ‘sides’ were, and who was on each, was something feminism was not ready to accept. At least, well, radical feminism.

Today, of course, we have a lot of feminists who see the word ‘feminism’ mostly meaning ‘fighting against gender inequality and discrimination’ — no matter what gender people are, or if they are cis- or transgender. The moderate group fully accepts not only transgender women, but even cisgender heterosexual males who wish to fight for exactly the same goals. They are not seen as being sent by the ‘patriarchal world-wide conspiracy’, but rather accepted as enlightened people (who cares what gender they are!) who understand the issue and wish to fight for the equality rights (no matter how much privilege they actually have; in fact, many feminist allies, being male, use their privilege to be heard by their peers — an advantage that they can bring to feminist activists).

Still, among feminists in general, there is this lingering feeling that women should stop — or at least downplay — the emphasis on their femininity. The idea is that, as long as femininity is appreciated by males, there will continue to be discrimination. Escaping from femininity, especially stereotypical femininity, ought to help the cause along. But obviously the moderate third wave feminists cannot deny a woman the right to look as she wants to look. They can just sigh in despair and shake their heads — but will comply with their options and choices, and eventually even defend them, even if they run contrary to mainstream (moderate) feminism, by emphasizing gender role differences instead of abolishing them.

When leaving the community of activists, ideologists, and philosophers, and entering the so-called real world, what I can observe is that third way feminism (and even some ideas of radical feminism) have, indeed, started to shape the way women think about themselves. It is perhaps not as obvious as activist feminists would like it to be — and certainly not so widespread — but one thing that has caught my attention is how women with a higher education, even if they have never read anything about ‘feminism’ in their lives, tend to adhere to the idea that women are allowed to dress and behave pretty much how they want, but ‘dressing up’ is considered a lower-class, no-education attitude by women with low self-esteem who bow to the pressures of the patriarchal society and self-objectify themselves.

Ok, perhaps I have gone a bit too far. It’s obvious that a lot of women do, indeed, enjoy looking great, and they do it mostly for themselves, not to attract potential husbands. But (and I have to remind my readers that my observations come from what I see on the streets of my own city, so this may not be universal) there is clearly a split between social layers — not always, but often also connected to higher education — in the way women dress and behave. Let me give you a few examples of my observations, and feel free to contrast them with your own experience, no matter where you live.

Feminism-induced gender presentation?

I realise that I’m bordering on political incorrectness in this article. After all, I’m also throwing around a hypothesis: that women with a higher education behave differently, regarding their appearance and overall attitude, than women with a lower education. This might not be well accepted in certain circles; I’m aware of that. On the other hand, it might also show the importance of education, and how, due to that education, people’s minds get shaped to think in a more progressive way. At least, in this specific case (how you present yourself to the public), there seems to be a strong correlation.

I’ll address a few counter-examples first, which actually seem to deny the hypothesis. Walking across what would be ‘the City’ in Lisbon — the area where there are most office buildings for banks and financial institutions, large corporations, fancy lawyer offices, and so forth — you can see most women dressed to the nines (to be honest, the same applies to the men as well). Forget ‘business casual’ — they wear ‘business formal’ attire, which includes almost invariably a formal jacket-and-skirt outfit, in toned-down colours (black, grey, or some light pastel), and a white blouse. The outfit is complete with high heels, of course, but of the formal type — nothing bright, no platforms, and so forth. The hair is worn long, silky, healthy-looking (although obviously the hair length will vary with the age of the wearer); makeup is discreet but always present; and it’s clear that all these women earn enough to spend many hours at the gym, at the salon, and at the plastic surgeon: they look bronzed and fit.

Now, these women have almost invariably a higher-than-average education; we are not talking about secretaries or receptionists here, but CEOs, lawyers, accountants, financial controllers, marketing managers, and so forth. These are the women who will be seated with high-profile customers in meetings most of the day, and work on expensive computers doing complex Excel spreadsheets. In effect, because in my country almost all women work (a stark contrast to most other European countries, except in Scandinavia, where many women still spend their time at home raising their children) — a consequence of low salaries — and, for the past two decades, far more women get a higher education than men, and they get this higher education in accounting, business management, international relationships, medicine, law, scientific research, and so forth — jobs that, not many decades ago, were exclusively held by men. As said, this is not because our country is especially progressive: it’s a consequence of very low salaries, half the European average or so, but with the same cost of living, meaning that both members of the couple have to work, and work hard, in order to pay their bills and give their kids a good education. Not surprisingly, most couples don’t have that many children: Portugal, with Germany and Japan, is one of the three countries with the lowest rate of births. This, in turn, means that the population is old — and the number of retired people is as high as the number of working people — which also means that all the highly educated and specialised workers are usually retired and it’s hard to replace them. What is the alternative? Well, because men are far lazier at studying these days than women (you’d be shocked to see the ratios of women studying — and finishing their studies — compared to men), it means that women get a chance to replace men at those higher-paying jobs, not because we’re especially tolerant towards gender, but due to the various circumstances that pushed women into jobs formerly only open to men — as an example, in the late 1980s, one of Portugal’s biggest commercial banks was on court for discriminating against women, since they refused to hire women for any position where they had contact with the public. Today, of course, after they naturally lost the court battle (they had no chance, really), this very same bank has far more women than men — not because the Board became more tolerant, but simply because it’s getting harder and harder to hire men with a higher education…

Anyway. This example seems to run contrary to my hypothesis. Indeed, it’s exactly on the higher middle class where women with higher education, replacing men’s jobs, ‘dress up’ (in a formal way) to the best of their skill and ability, and take good care of their personal appearance. These same women, very likely because of habit, will also roam the malls and leisure areas during the weekend quite ‘dressed up’ — changing, of course, their formal business attire to casual dresses of expensive brands. But I would argue that this is really just a question of habit. In fact, it’s the dress code in their corporations that pushes them to ‘dress up’ — not their own choice (even though they do not openly protest against the dress code; the women I know that work in corporate offices actually like to dress that way, they only complain about the high heels). And, truth be told, the same rigid, formal dress code also applies to men as well — anything less than a dark business suit and a tie is pretty much forbidden (even in summer).

As a side comment on the rigidity of the dress code, there is a fun story that happened a few years ago. The previous government had to deal with the effects of the financial crisis, and that meant the government had to save money as much as they could. One decision was to turn the air conditioning down during summer. Government workers, who are used to a relatively strict business dress code as well, were ‘allowed’ not to wear ties during the crisis, and could take their jackets off while working, since it would be more uncomfortable for them otherwise. This was the source of some fun in the media, but it shows how the upper middle class in Portugal is so used to formality in their dress code that this measure to save money was accompanied by a relaxation of the dress code — which needed a law for that!

Another exception is worth mentioning: clubbing, parties, special events. In the late 1980s, people would dress as casual as they could when going out for leisure. These days, however, it truly amazes me how much time and dedication is spent by women when ‘going out’ — not to all places, of course, but to those I mentioned. ‘Dressing up’ in those places is transgenerational; in fact, I might believe that millennial women even take more care with their appearance, but, of course, this just pushes older women to do the same in order not to look ‘out of place’ — even those women who, twenty years earlier, would not even consider wearing a dress or putting on high heels, and who had discarded makeup as something futile. It’s also interesting to notice that in these places, caring for your appearance has nothing to do with your social status, class, race, creed, age, whatever… everybody is at the same level, and every woman will dress as best as she can. Obviously there are exceptions — more radical and alternative nightclubs, for instance; even though I noticed on a famous hard rock nightclub (the kind where at the end of the night people still smash things around) how most women (not all, but definitely many) took great care about their appearance, even though they might wear more leather and spikes than usual…

So… describing two examples where social norms somehow imply ‘dressing up’ does not mean this is the rule. It just shows that society’s norms and fads and trends still have an influence, no matter how strong feminist ideals have been widespread. But now let’s analyse the rest of the cases.

Walk across the streets of Lisbon, or the leisure spots during the day, and it’s very easy to spot the difference of social status. Again, it has nothing to do with having money or not, but with the kind of education you got: the lower the social status, the more likely someone will have been raised according to very conservative (and sexist) moral values, and, having little education and no drive to learn to think for themselves, people will tend to adhere to established historic stereotypes. This is quite clearly seen on places where there is a considerable difference of attendance depending on education. For instance, if you go to the theatre for a play, or an opera, or a classical/baroque concert, women there will be wearing casual attire. A few might be a little more dressed up than usual, but, in general, they will simply pick up something that fits them well. During evening events, their clothes may perhaps have a little more ‘bling’ — just a slightly more shiny fabric, for example. Some older women might even wear a nice pastel shade of lipstick. That doesn’t mean that women will dress sloppily — this was true in the late 1980s (how well I remember that!), but not today. They might even wear dresses, especially on hot summer nights. They might have fashionable sandals with a little bit of heel. Their hairdos will show that they regularly go to the hairdresser — their hair is shiny, healthy, taken good care of. But that is as far as it goes.

The same, of course, will be true of any working place (except those mentioned before). The higher the education needed to perform some job, the less women will conform to typical stereotypes, both in dress and appearance as well as in attitude and personality. Female university professors, to make sure they are really female, you will need to be very close to them 🙂 Well, perhaps this is a slight exaggeration, of course, but what I mean is that most of them will pretty much ignore all social conventions and stereotypes. The same will apply, to a degree, to school teachers as well. A special case are doctors, nurses, lawyers, judges — they wear the equivalent of an uniform when on their workplace (as do males), but, outside of the workplace, they will wear casual clothes and never overdo their appearance. Again, there is a difference between being sloppy (university teachers tend to be more sloppy!) and dressing outside conventions. There is a casual style for women which is at the same time feminine — in the sense that they are not unisex or designed specifically for males, but they have been designed having the female body in mind — and very casual. A male wouldn’t classify that kind of dress code as sexy — clearly, these women are deliberately stepping outside stereotypes, and the fashion designers have responded in kind: I would describe this casual style as ‘looking good without sexual objectification’, that is, there is still a difference between male and female attire, but that difference is mostly due to different body proportions, not because female clothing is designed to look alluring, attractive, sexy, or anything fitting into a male-created stereotype. It is not sloppy nor even boring. It can be fun!

We can here see clearly the influence of feminist activism in place: these educated women, often with a good career and financial independence, do not ‘dress to impress’ anyone. They do not bow to the patriarchy; they refuse to conform to stereotypes or male expectations. But they aren’t ‘imitating’ men; they might borrow some inspiration from their attire and attitude, but, instead, they have carved their own identity niche: the notion that women can still be women (and enjoy being women) but without conforming to social expectations.

The contrast with the kind of clothes they might wear on a clubbing night is brutal!

Now we can go a bit lower on the social class, and here we start to see big changes. A typical example: shop attendants, especially on supermarkets and similar places, even if they often wear a uniform, they will take good care of their appearance — almost all of them will wear makeup (more or less according to taste), take care of their skin, paint their nails (sometimes exaggerating the nail length or the amount of nail art they carry), wear rings, bracelets, and so forth. They will be nice and pleasant to talk with — what you expect from people interacting with the public, after all — but you can see a lot of the male-dominated mentality influencing the way they dress or behave. A good example is noticing how the owner of a beauty salon or a cosmetics shop will carefully select all his female employees to have big breasts and a slim figure, and, if they do not use an uniform (that obviously depends on the shop), to wear on a daily basis something that reveals their figure — not necessarily in a ‘slutty’ way, of course, but definitely far more revealing than the ‘casual look’ explained before. Bodycon dresses are, for example, quite welcome (even if they don’t show any skin, they will most definitely reveal all curves…). Interestingly enough, this seems to be more true on places more attended by women than men, something which runs contrary to the usual expectations. My only explanation is that such places are owned by men who would love that his customers would conform more to a typical stereotype, and, therefore, they ‘show off’ their employees in a way that they hope customers will imitate — this is naturally more obvious on clothes shops, beauty salons, cosmetics/makeup shops, and so forth.

And if we go even lower than that, we will find a social class where women are little educated and might not even be able to hold a job requiring no qualifications for a long time; unfortunately, that means that these women will do all their best to conform to stereotypes designed to allure men to marry them, so that they can be financially supported by them. And yes, this means dressing sexy all day long, and spending hours on beauty salons and the like. While this is not widespread — not any more, at least in my country, where, as said, women have, on average, a much higher education than men — it is quite common among certain communities, where, due to cultural bias, from a much more sexist perspective, young girls in marrying age are expected to look as slutty as possible to quickly attract men, get married, raise children, and do nothing else but look beautiful to keep their men around as long as possible. This is unfortunately still the case — at least in my country — for a reasonable percentage of the female population. Of course, with successive generations, the children of those communities will get an education at school, many will continue towards higher education, and, as they learn how to think for themselves, they will quickly discard the sexist stereotypes and adopt the casual look of the higher educated women (because they will now identify with that group, as opposed to the community they have been born into).

So there is a trend which is quite visible, and the correlation is very strong: adherence to sexist stereotypes is closely connected to education. One might imagine that ‘money’ would also play a role here, but it doesn’t. The lower class women spend all their money in getting beautiful. If they come into money — a typical approach is getting married to a star that came from the same social class as them, but became popular and started earning quite a lot (think about music stars, soccer players, and so forth) — they will still keep their ‘sexy image’, but, thanks to having much more money available, they will be able to improve themselves through multiple surgeries, getting more expensive-looking clothes, and so forth. In terms of looks, in spite of all their money, they will not dress and behave differently from their peers in the lower classes. The reverse is also absolutely true: you can have a higher education but no money whatsoever (alas, after the crisis, this is certainly the case…). Such women will still dress casually, avoiding any stereotypes, even though they might have to stop shopping at expensive brands and just look for clothes in similar designs from cheap brands or from the Chinese boutiques, where clothing is really very inexpensive and quite affordable, even though the quality, obviously, will be quite low. But what matters is that these women will still be able to dress according to their education, and not according to how much money they have.

This is actually an interesting reflection about society in general — how education shapes behaviour (and appearance), while having more or less money seems to be irrelevant — which might be interesting for a sociologist or anthropologist. In my case, however, I was only curious in observing where stereotypes are still maintained, and where they have been discarded, and what has caused the change. It was also quite interesting to observe the exceptions.

The best example of all the above is seen among immigrants, mostly those coming from Brazil or from Slavic countries in Eastern Europe. I’m well aware about how sensitive the migrant issue is in these days, but Portugal is a strange country in several senses, and one of the reasons for that is that we are the country with the oldest borders in the world, so we give little importance to things like ‘patriotism’ or ‘defending our borders’ (well, except during international soccer championships…); we are such a mix of different people around the world that, while there is allegedly a ‘Portuguese ethnicity’, it clearly has changed so much over the centuries that it is rather uniform (genetically speaking). As we tend to say, there are no Portuguese without Jewish, Gypsy, African, or Maghrebin/Arab blood — it just gets thinned down over the centuries and becomes unnoticeable after many, many generations of intermarriage.

Brazilians and Slavs coming to Portugal are often middle- to highly educated, but come from relatively sexist societies, where women are still expected to ‘dress to impress’, get a husband quickly, marry and have kids. Obviously this is a generalisation, and there will be more exceptions to the rule — individuals are individuals — but, again, because such conservative and sexist ways of thinking are much more predominant in those countries of origin, it will show in the way they dress and behave. It’s quite easy to spot those women who have recently arrived to our country — they will wear lots of makeup, dress to show skin, often in impossibly bright colours, and wear the kind of high heels that we don’t even see on strippers around here. But this will quickly change. Portuguese culture is also strange, and it revolves mostly around food and going to the beach (for all genders), and, in general, to live in a way that avoids getting into trouble with neighbours. This will slowly change the behaviour and attitude of those living in Portugal for a year or so. It’s quite noticeable — after a year, Brazilian and Slavic girls will stop wearing makeup and just adopt the exact kind of casual clothing of the other women around here. They will become completely invisible — you will only get a hint at their origin from their accent, but that will be all. In fact, it still shocks many Portuguese (but for the right reasons!) seeing how the Ukranians, for example, are quite fond of dressing up in Portugal’s colours and wave Portugal’s flag every time there is a world soccer championship around — and they will go to the same places, watching the games on esplanades in front of a few beers, and yell as enthusiastically as the ‘natives’ here. There is a strange notion around here (but, then again, this has been happening for over eight centuries) that if you absorb the fundamental points of our culture (which does include the love for food, beach, and… soccer), then you’ll be totally accepted, no questions asked. And you can see this happening very, very quickly among the Brazilian and Slavic communities.

Even in the Chinese community — traditionally very conservative, very closed upon themselves — you can start seeing a big difference, curiously more noticeable in their body language. Different cultures have different body language, of course, and the more different the culture, the more noticeable those differences will be; but second-generation Portuguese-born Chinese will start adopting more of our body language, and less of their parents; and this is slowly becoming visible. It’s hard to explain what the difference actually is, but you’ll notice it once you see it!

So, although Portuguese society might not be overwhelmingly multi-ethnic, there is enough variety to observe the differences. And you can notice that, as communities become more conservative and male-dominated, women from those communities will ‘overdress’ — they will become hyperfeminine. The notable difference comes from the ultra-conservative societies (as the Chinese or the Pakistani) where women initially will wear very subdued clothing. But over time — and across generations — we find the same thing happening over and over again: the more male-dominated the community is, the more hyperfeminine are the women in those communities.

This has also the reverse implication. Because Portuguese women, in general, tend to reject ultra-conservative, male-dominated communities — 50 years of a very conservative and patriarchal dictatorship made contemporary women go for the opposite! — they tend to dress to show that they have left this conservatism behind. And one way of clearly showing that is by rejecting sexual objectification, and, therefore, rejecting all hyperfemininity. But it goes a step further: in order to distance themselves from the lower classes (usually more conservative) and the conservative ethnic minorities, the average Portuguese woman — especially those with an education — will try to avoid dressing in the same way. ‘Dressing up’ — being hyperfeminine — is therefore a sign of a lower social status and/or belonging to a conservative, backwards-thinking minority. It might sound strange, when we contrast that with the glamour of the movies between the 1930s and the late 1960s, when women would always be hyperfeminine, and they revelled in their femininity — while the lower and lesser educated classes would dress in a much more demure way. Today, things are exactly the opposite!

The exceptions again… and the transgender community

One might therefore ask why there are exceptions to the rule. In the male-dominated corporate world, well, we can imagine that the dress code is enforced by the males sitting at the boards (they still are an overwhelming majority), and, therefore, they demand their female employees to deliberately engage in hyperfeminine formal business attire. So this exception is easily explained.

What about going out, clubbing, attending concerts, and other social functions during nightly leisure activities— especially those with a large audience? It’s not so easy to shrug off this exception, especially because you can see that it applies to all social classes, all ages, and all communities (well, I haven’t been to a Chinese-only nightclub… I have no idea if they exist at all in my home city… so I can only describe what I saw so far). There is somehow a ‘suspension of social norms’ in such places, and, strangely enough, being hyperfeminine is ‘in’. The same applies to the beach, for instance, where women will show off (and for you Americans, remember that over here in Europe women are allowed to go topless if they want — even though much less people do it than you might think 😉 ).

One might be tempted to argue that this is because those women are looking for potential partners, and therefore they are dressing in a way to captivate them. I think that such an explanation is far too simplistic, because girls will go with their boyfriends, women with their husbands, and they will all dress up, no matter what their relationship status might be. Granted, some single women might take extra care about their appearance, but I would not really say that this is truly noticeable. I would consider the alternative explanation: on those occasions — as well as on marriage ceremonies, baptisms, gala events, and so forth — people simply want to look their best, and this — in the case of women — means falling back to hyperfemininity.

But I will argue that it’s still not that simple. Certain events stopped being ‘ceremonial’ — going to the theatre, to the movies, to a classical concert or opera, etc. — and women are much more relaxed when going to those events; while on others (gala events, especially when transmitted on TV networks) they still dress up in a hyperfeminine way, sometimes outrageously so. And going to a nightclub, which in my youth was something you do merely to relax, to have fun, to spend a good time, and therefore you would simply grab whatever was still clean and wear it, are now the pretext for women going over the board with their appearance. So there is probably much more than merely ‘sexual allure’, but more likely changing social conventions. I believe that the real reason behind that is that casual, sloppy wearing is used mostly as a statement — refusing, on a daily basis, to conform to male-induced stereotypes — while ‘dressing up’ for those social events (and not others!) is merely what women like to wear, pretty much ignoring what the male-dominated society has established as ‘appropriate’ dress code for women. But I have no basis for either confirming or refuting my hypothesis; the few cisgender women I have asked them about their reasons are usually silent about it; they just say ‘because that’s what we currently do’, without giving an argument; or they shrug it off saying that ‘it takes too much time to dress up’ (even though being aware that women in the lower classes working at supermarkets will spend that time every day — as well as the highly educated women working in the corporate environment — so ‘extra time’ is, to my ears, just an excuse); or perhaps they simply don’t wish to confide in me, believing I might not understand their reasons. Of course I cannot generalise; there are some women, like my own wife, who would never ‘overdress’, no matter what the social occasion, and she would give a billion valid reasons for her choice (one of them, of course, being the claim that she has freedom of expression and dresses pretty much as she wants, and not as others expect it from her).

So where does this place us MtF transgender people?

Ultimately, we can all agree that it’s not the clothes that make the person. However, it’s no less true that we cannot read people’s minds, so we will need to infer from external signs — body language, attire… — what they are thinking. One of the reasons for the binary gendered society having invented different attire for each of the genders is that this makes them easier to distinguish; after all, we are supposed to figure out easily enough with whom we ought to mate in order to reproduce. The other reason, of course, is using clothes to hide what is not so attractive, and to enhance those attributes that are attractive — thus becoming more attractive in the eyes of a potential partner. Naturally enough, what is ‘attractive’ changes across societies and eras, although, perhaps a bit surprisingly, there are certain fixed attributes (ratios between distances on the head, for instance) which are universally attractive. This has been researched over and over again, and there seems to be a strong correlation between such ratios and the level of attractiveness; short of surgery, the only way to come closer to those ‘ideal’ ratios is via makeup and appropriate clothes (and shapewear!).

Now, we humans are very good at pattern matching, at recognising faces, at reading micro-expressions. As such, from very few hints, we usually can figure out someone’s gender almost immediately. This is naturally the result of eons of natural selection; we’re supposed to be good at that, since it’s fundamental for reproduction. Thus, even very ugly women will be seen as women, no matter how attractive or not; even very ugly women will get sexual partners and establish enduring relationships. That’s just because no matter how ugly a woman might be, she will still have certain proportions and ratios that will immediately identify her as a woman — no matter what she dresses, either.

My wife tends to describe this very clearly by saying that she always identifies as a woman, no matter how short or long her hair might be, no matter if she wears makeup, no matter how ‘feminine’ or ‘masculine’ her current choice of clothes might be; she is a woman, no matter what; and it’s not even a question of genes, or hormones, or internal chemistry — because she is quite unfortunate and has lots of hormonal problems as well as some autoimmune diseases. It’s a question of an essence of femininity that she has — an intangible quality, possibly an epiphenomenon of some sort, which she possesses but males don’t.

This, naturally enough, is very arguable (and I will always be the first to argue with her about that!!). But let’s suppose, for a moment, that my wife’s assertion is correct.

If so, then we would have to find that ‘essence’ present in MtF transgender people as well, since they identify in being women as well. However, their bodies have all the wrong proportions and ratios — some of which can be changed with hormones, some only with surgery, and some (like the width of the hips) not at all. But even before such therapies and surgeries, if someone possesses this ‘essence of femininity’, then that person would be a woman — and recognised immediately as such — no matter what she looks like physically, no matter what she wears, no matter what her body language might be. The ‘essence’ ought to somehow shine, reveal itself to others, in the same way that my wife’s essence proclaims her to be a woman, even if she’s not a particularly attractive one, and definitely does not ‘dress up’ at all.

We transgender people know that this is not the case — not at all.

Indeed, to refute my wife’s arguments, I usually point out to her that this so-called ‘essence’ that she claims to exist is only available to cisgender women during a certain period of their lives — namely, between puberty and menopause (more or the less). Very young girls will look like boys (and vice-versa), and the older you get, the differentiation will be small again. Dress a 90-year-old woman who didn’t go through extensive surgeries in male clothing and it would be impossible to figure out what her gender is.

We can argue that this is exactly as nature has intended — that the physical difference between genders is only necessary during the phase in their lives when both are able to reproduce themselves, and this would be consistent across other species where there is a strong gender differentiation. I’ve addressed this issue before — not all species have pronounced differences between the genders. Cats are a good example — male and female cats are almost impossible to distinguish, and this will be the case from birth until death. On the other hand, species like, say, chicken have marked differences between genders. Homo sapiens is somewhere in between the two extremes: we are not that different (in the sense that there is an overlap, i.e. the strongest women will be far stronger than the weakest men, for example; the tallest women will be much taller than the smaller men, and so forth; it’s just when we measure averages that we see a difference between the genders), but we are different enough, and this is more noticeable during our reproductive stage.

And the differences, as said, can be minuscule — because we humans are so incredibly good at pattern matching that we can very easily spot that difference, even if we are unable to say what it is. A typical example: women, on average, have larger eyes than male — considering all other proportions. Obviously there are men with large eyes, and women with very small ones — but those are exceptions. Male eyes are often much more deep set, there is a more pronounced forehead bone (blame that on the Neanderthal genes we’ve inherited!!), and even in absence of any body fat, the female jaw line and chin are much softer and more rounded than the male one. Obviously we can find a lot of exceptions here, and, as said, such differences will be much less noticeable with increased age, but the simple truth is that we are really very good at spotting those differences.

So, therefore, even though one might argue (as my wife does) that MtF transgender people may have an ‘inner female gender core’, this intrinsic femaleness, in general, will not be visibly externally (this is one of the reasons for gender dysphoria, of course). MtF transgender people, therefore, in order to best ‘fit’ in society — preferably by becoming invisible — will try to make an effort to disguise those traits that immediately point them out as not being female (at least physically!). We are lucky, because we have invented so many forms of doing that — from makeup to clothes, from shapewear to hair styles, women over the eons have come up with all sorts of tricks to minimise their faults and emphasise their best points, and we MtF transgender people are able to do pretty much the same, sometimes with good results.

Many crossdressing books or online advisors tend to write things like ‘women, just like men, come in all sorts of shapes and sizes’, thus trying to tell MtF crossdressers that there is no such thing as ‘perfection’ and that even cisgender women will have to struggle with their bodies in order to look closer to a so-called ideal stereotype. So MtF crossdressers just need to pick up those very same tips and tricks. Yes, it means they cannot wear everything, and that some hair styles will be absolutely no-no for them, but the same will also apply to an uncountable number of cisgender females, so that’s ok.

What those books and advice do not say is that, in order to do so, it means always going a bit towards hyperfemininity. Now this is no problem — at least in my country! — if you wish to go out clubbing, because it’s expected that all women there (cisgender or transgender) will ‘overdress’ in a hyperfeminine way. But what about the rest of the day? What about the social prejudice that exists if women ‘overdress’ during their daily routine? This is one of the reasons why many crossdressers, when found outside their ghettos, will be pointed out as ‘slutty’ or merely ‘lower class’ — because, in their struggle to hide their more male characteristics, they will almost inevitably slip towards hyperfemininity, which carries a social stigma as well; one that might, to a degree, be even worse than being transgender: if I understand the reasoning behind my wife’s own thinking, her argument is that transgender people who overdress are merely approaching that male-induced hyperfeminine stereotype, and, therefore, revealing themselves as the males that they (still) are — because cisgender women would never dress that way.

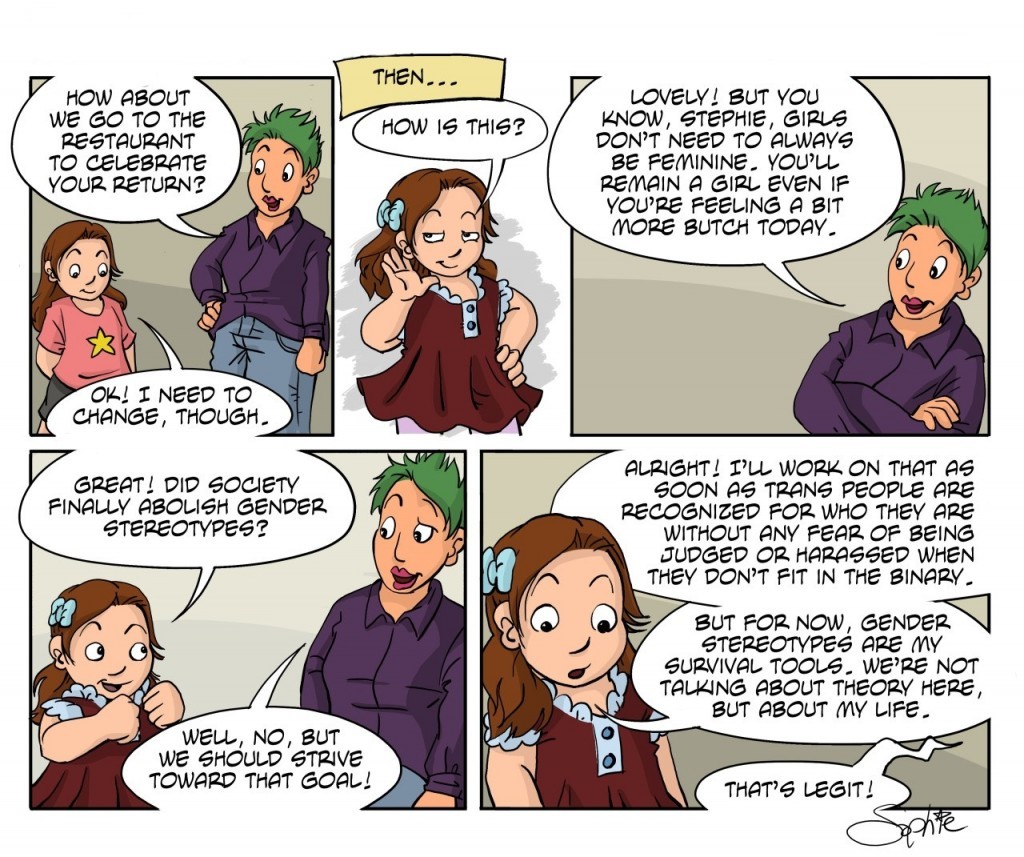

She might be right. But what choice do we have? The following cartoon is my only defense:

I’m fully aware that the author of this cartoon (Assigned Male), Sophie Labelle, has a very strong political agenda (and uses cartoons and webcomics to promote them), but that doesn’t mean that sometimes she isn’t right! In this case, what Sophie is pointing out is that MtF transgender people might not even have a choice in what they wear, no matter what their actual ideas about attire might be.

The argument is simple: the average MtF transgender person might not be physically similar enough to the average cisgender female to be able to ‘pass’, or, if that is not even possible, at least not to draw unwanted attention from other people. I’ve addressed the issue of transgender invisibility before, so I will not do it again; it suffices to say that, in order to minimise the risk of transphobic comments or even violence, transgender people very often do a deliberate effort to not raise attention to themselves.

Of course this is not universal — again, there is the risk of generalisation! Some crossdressers, for instance, deliberately like to push the social norms and adopt a ‘drag queen’ look to provoke onlookers into a reaction; some transgender activists also deliberately adopt a dress code to ‘stand out’, also as a counter-reaction to society’s norms and rules. And, of course, there are those who do not really want to pass a message and/or make a (political) stand, but simply dress whatever they actually like to wear.

But it’s nevertheless true — and we have gazillions of pictures of transgender people on the Internet to prove this argument — that a large number of MtF transgender people will make a deliberate effort to ‘pass’, and this means, in general, trying to achieve a feminine look that is consistent with the usual dress code worn by women in their society and/or community. They will also desperately try to ‘hide’ their more ‘male’ features, and this, in turn — not unlike women who need to do the same, not having been lucky to be born with supermodel figures — often means ‘overdoing’ one’s look, i.e., entering the realm of hyperfemininity.

This naturally poses a problem, as Sophie’s cartoon explains so well. By pushing into hyperfemininity, even if ‘toned down’, MtF transgender people might look more like the gender they identify with (and this is because hyperfeminine attire enhances, in several regards, those feminine attributes that MtF transgender people are so desperate to show; while at the same time downplaying the masculine attributes), but, because women do not dress that way any more, they will nevertheless stand out.

What is the alternative? I have met several transgender people who simply don’t care what they wear, and adopt the casual, almost sloppy outfits that are favoured by women in our society in most social activities. The problem is that this kind of look will invariably hide whatever feminine traits they might wish to enhance, while making their masculine attributes stand out. Cisgender women, of course, can get away with it, because, well, they will always be recognised as cisgender women, no matter what they dress; transgender women, however, have a serious problem in that regard. They can only resort to aggressive demands that people treat them as the gender they identify with — even if they do not look even remotely like that gender — and appeal to people’s understanding. But they will have to deal with cognitive dissonance: for all practical purposes, they will be ‘men in a dress’ (and not good fitting dresses, either), dressing sloppily, ridiculing the prevalent feminine image (because they simply do not look ‘feminine’ enough in such clothing), and, in short, drawing all attention to them — even if, in fact, they are adopting the prevalent style of dress that cisgender women usually wear.

This naturally poses a complex dilemma: for MtF transgender people, it’s a lose-lose situation. Go for hyperfemininity, and you will draw attention to yourself, not because you don’t look like a woman, but because women do not dress that way (except for those special cases mentioned before); go for the casual, sloppy look that women prefer to wear these days, and you will draw attention to yourself, because such clothing will enhance your male attributes and downplay whatever female attributes you might have, and you will just look like a clown, a parody of a woman. There is no middle term — unless, of course, you have started with androgynous genes and can easily dress whatever you like, because it will always fit you well. Naturally enough, those are exceptional cases — most MtF transgender people do not look remotely as good as that — but unfortunately the media (and even the Internet!) will show far more pictures and images of those transgender people who already look perfectly like the gender they identify with, than the images of the vast multitude who just ‘looks wrong’, due to no fault of their own, of course.

TERFs might even have a point (at least my wife does)!

One of the reasons why transgender-exclusive radical feminists are so much poised against transgender women is simply because they claim that they are ‘not really women’ but ‘men shot up with hormones and dressed as women’. Of course things get more complex, ideologically, and extreme radical feminists will go as far as saying that transgender women are merely a ploy by the patriarchal society to ‘infiltrate’ the feminist movement and impose ‘their’ definition of what a woman is. While this is obviously a paranoid delusion, and not even worthy of a reply, there are at least two other points that they raise that are actually not so stupid.

The first, of course, is the problem about defining ‘what is a woman’. When a woman identifies with being a woman, what does she actually mean by that?

This has been a good source of philosophical discussion between me and my wife, and, to a lesser degree, between me and my psychologist. My wife’s claim is that she is (and identifies with) being a woman, no matter what. And she really means that: she couldn’t care less about the way she behaves, the way she talks, the interests she has, what she dresses or how she looks like — all that, for her, is superficial and irrelevant. She knows she is a woman, and that’s what matters. Sexual and reproductive organs, working or not, don’t even matter (her reproductive organs are a mess, and she has thyroid problems, meaning that her hormones are not exactly at the correct levels…). There is an ‘inner essence’ somewhere deep inside her self which tells her that she is a woman. Not even going into Buddhism philosophy, claiming that the self does not exist by itself but is really just a mental construct, will demolish my wife’s absolute, unwavering conviction that she is a woman: Buddhism also explains that, even though the self does not exist by itself, it is created due to causes and conditions, and there are certainly causes and conditions (whatever they are; the mere fact that we don’t know them doesn’t mean that they do not exist…) which made my wife’s self to be undoubtedly female, and self-recognising and self-identifying as female. One can argue that this comes from whatever embryological changes have been made to the brain — or from genetic effects — or from not yet fully understood reasons; whatever the real reason might be, it’s irrelevant for my wife: she knows she is a woman, with the same conviction that she knows she’s a human being of the species homo sapiens, and not a mutant alien from outer space just happening to assume a humanoid form.

Buddhism, in fact, even though not really worried about gender identity, gives us some examples of how this kind of conviction works. And yes, this is once more my chocolate example. Before you ever tasted chocolate, you might believe that it is tasty, because others have told you so. That belief might be extraordinary, to the point that it will be hard to shake, if someone you trust completely and has never, ever lied to you (or deceived you in any way) will tell you how tasty it is. But still you might get a contrary opinion from another person that you also trust as much; in that case, your belief might be shaken, or at least you might start questioning yourself (and those who tell you that chocolate is tasty — are they right after all). But there is a point where your conviction about the tastiness of chocolate will be unshakeable: it’s when you taste it. From then on, you do not need to rely upon an authority to tell you chocolate is tasty: you know that, because you’ve been through the experience. Buddhism is very keen on gaining convictions by experiencing things (and getting trained to make sure that your experiences are not clouded by your perceptions, of course): ultimately, the only way to know that Buddhist techniques actually work is not by having faith in the Buddha or in a good teacher or in the many books written about the subject — it’s by experimenting those techniques and seeing how they work for yourself that will make you sure that they work. Trusting authorities on a subject can only go to a certain point, but not beyond.

The same, of course, happens in science — you might only implicitly trust authorities on a subject before you really start studying that subject and conducting (or replicating) experiments. But once your own experiments validate what the authorities have written about the subject, you don’t need to rely on them; instead, you rely on the scientific method which allows you to validate any scientific result by yourself — and only that way you will have an unshakable conviction that the subject is, indeed, correct.

Therefore, my wife does not need to read books about how women feel or act or behave or even dress; she does not need to rely on ‘authorities’, i.e. others telling her that she is, in fact, a woman. She does not need to rely on feminist ideology to define what a woman is and what a woman is not. Because my wife experiences the world from the perspective of a woman, and she knows she is a woman in her core, she has absolutely no doubt whatsoever. A million people (I imagine a crowd of radical feminists, each with their own definition of what a woman is supposed to be, knocking at our home) can try to persuade my wife otherwise, but there will be absolutely no argument that will change her conviction. And even if she cannot describe what it means to ‘be a woman’ she is quite aware that other women experience exactly the same as she does (even if they cannot describe it either, or if their own descriptions do not exactly coincide with my wife’s). Again, it’s like the chocolate example — you can describe the experience of tasting chocolate to the finest detail, and someone who never tasted chocolate will never ‘get it’, but anyone else who has eaten some chocolate will immediately understand your experience perfectly. They might describe it differently — for some, chocolate might be bitter, for others sweet… — but they are perfectly aware that the experience of tasting chocolate is the same. We just fail at describing non-cognitive experiences.

Now, taking all the above in account, I had to answer truthfully to my psychologist when she asked me if I felt that I was a woman — if I identified with being a woman. I hesitated. Unlike my wife, who has the experience of being a woman all the time since birth, I have a different experience. So, in all truth, I cannot say that I’m a ‘woman inside’. How can I know? I only recently experienced society from the perspective of a woman (‘recently’ in terms of my almost-half-century of existence upon this planet). Ah, but transexuals might have felt that they are ‘female inside’ since birth. So why I’m different?

Well, because all I can say with honesty is that people have told me all my life that I was supposed to be ‘male inside’, but I reject that — I’m pretty sure I’m not. At least, I’m not ‘male as others think that male people should be’. I’m not ‘male according to society’s stereotypes’. I’m clearly ‘something else’. Because, in general, I think that binary gender roles are useful (I might explain this better one day), even if gender is not really binary, I reason the following way: ‘I don’t know what I am; but I’m pretty sure I do not identify with “being male” as other male people do; I’m different from a male; therefore, I have to conclude that what I am “deep inside” is female, and not male’.

But this, as you all know (or should know by now!) is an absurd simplicism.

Gender not only is not binary (i. e. nobody is 100% male or 100% female) but it is not an exclusive attribute, that is, if you’re 70% male, then you must be 30% female. It does not work that way. My wife might be 100% female, for instance, but she is also perhaps 70% male — this is because from any list of attributes of ‘maleness’ (excluding physical attributes, of course) my wife will very likely have almost all of them as well. So, to make matters confusing, there is no right answer to ‘Are you male or female?’ — because that implies a binary gender. Which is clearly something that does not exist.

However, there is still one way out of that complex question. And this is separating identity from expression. While there is no binary gender identity, at least in most societies, we still have a binary gender expression. Yes, I know that the borders between both are fading. But this article on hyperfemininity would not make any sense if we could not define what hyperfemininity is.

So, my answer to my psychologist should have been something different: ‘I don’t know if I’m male or female, but I certainly don’t identify with the male gender role — I just have to prod along with it because I don’t really have a choice — and I totally identify with the female gender expression.’ That’s sneaky me, right? Right. I’m totally avoiding the complex issue!

Therefore I can answer truthfully to TERFs: look, girls, I have no idea who is allowed to define what a ‘woman’ is and what is not. I also have no idea if I’m a ‘woman’ according to any of those definitions. All I can say is that there are male gender roles, and female gender roles, and I don’t like male gender roles, and prefer female gender roles. And with those gender roles there comes a gender expression. I hate the male gender expression, and I love the female gender expression. Now, what that actually makes me, I have no idea. You can still call me whatever you like. Yes, I have XY chromosomes, but that’s nothing I’m proud about. Whatever you say or claim, I can only say that I identify with the female gender role, and I identify with the female gender expression. That’s all I know, and that’s all I can say.

And they can jump on me and yell: ‘Aha! We knew it all along! You’re not really a woman! You are just pretending to be one by adopting their gender roles and expression!’ And I can only shrug and comment: ‘Yes, exactly like half of the human population, who also pretend that gender is binary, and that, by following the female gender role and the female gender expression, they will be recognised and treated as women.’

In other words: what I’m doing is pushing the definition of what ‘man’ and ‘woman’ means in this age of fluid gender and sexual attributes to my own field, and merely state something which ought to be obvious for transgender people. And I can summarise it all in this way:

There is no binary gender; there are no binary sexual attributes; there is no binary sexuality; all is a spectrum, and each of us has a little bit of everything.

Therefore, in our western societies, we have to define ‘man’ as someone who identifies with the male gender role (as defined in this society) and the male gender expression (as the current fashion determines); ‘woman’, by contrast, is someone who identifies with the female gender role and the female gender expression.A transgender person is someone who, at birth, has been assigned a role and a gender expression that just feels ‘wrong’ for them because they do not identify with it. Gender dysphoria are a series of symptoms occurring from the difficulty in dealing with the daily dissonance of what one wishes to adopt as a gender role and expression, and what society forces one to adopt. ‘Transition’ is mostly a legal process, optionally accompanied by a medical process, whereby one adopts the gender role and/or expression they identify with, and is released from the social conditioning to adopt a gender role and/or expression they do not identify with.

Take that, you TERFs! Hah!

All right, I know these definitions are also flawed, since they move away from whatever the ‘inner gender core’ might be, and rely on a binary exterior appearance (and behaviour, such as determined by a role). And as we so well know, these days, on most societies, there is a huge blend between the gender roles and appearance. So does my definition accomplish nothing?

Well, yes and no.

Hyperfemininity as a function of transgender role/appearance identity

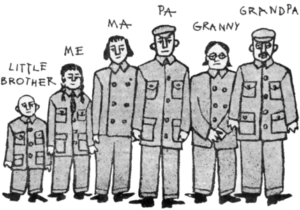

Suppose that we lived all in a world where Chairman Mao had conquered every other country and placed it under his single government and rule, and forced both genders to adopt the Mao suit as the only approved form of garment.

Suppose that we lived all in a world where Chairman Mao had conquered every other country and placed it under his single government and rule, and forced both genders to adopt the Mao suit as the only approved form of garment.

The question is, can you find the difference between the genders that way?

And the answer, of course, is that it depends. Women’s bodies are different from men’s, but not that different: just different enough, and, as said, this is what makes us humans, excellent pattern-matchers that we are, to spot those differences and focus on them. On the cartoon to the left you could immediately see which ones are the males and which are the females, even if the characters hadn’t any titles hovering over them. Sure, there would be some cases where you might have some doubts (and the uniforms in the cartoon are not, well, uniform… women’s suits on the cartoon, at least on the older women, have a slightly different design). But, in general, most of us would pick the genders apart, even if we all wore Mao suits.

A crossdresser in that world would have it tough to ‘pass’ — because I’m pretty sure that makeup and wigs would be unavailable for sale, and men would be constantly watched, so that you would not even be able to grow your hair long enough to disguise yourself, even if you managed to steal a Mao suit that was appropriate for women. But maybe a few people with a truly androgynous appearance might pull it off.

So here is the catch: in our human society, we are especially good at figuring out who is male and who is female (remember my previous article? Yep, we’re conditioned by Nature to be very, very good at that). Although a few of us are lucky enough to be close to the middle of the spectrum to ‘pass’ for either gender, the truth is that most humans are not androgynous (exactly because Nature will tend to favour those who have clearly defined secondary sexual characteristics). And that means that most of us will need some help from cosmetic technology, shapewear and fashion design (some cuts will fit us better and disguise our most prominent male characteristics) to be able to look like the gender we identify with.

Now this is naturally a problem. Because for the past decades (well, at least since the late 1970s) the ongoing fashion is for women to look ‘natural’ — and this, as explained at the beginning, means favouring casual looks and disregarding makeup and/or other enhancements during most social events — crossdressers will ‘stand out’ if they really need a lot of ‘enhancements’. In other words, like on Sophie’s cartoon, we will tend to favour a slightly outdated and overdressed look, because that’s what will fit us much better and disguise us best.

But this, in turn, reinforces the idea brought by radical feminists — and even some more moderate ones — that, somehow, transgender women are not ‘women at the core’ because they need to hyperfeminise themselves in order to be accepted as women. You see the dilemma here. Of course transgender women do not need (in the sense that they are somehow coerced…) to ‘dress up’ to validate their ‘inner female core’ — just like cisgender women. The difference between both is that transgender women also need to be validated by others as women in order to be fully functional as women in society. And that, unfortunately, unless you happen to have been born with a fantastic genetic makeup, means ‘dressing up’ — at least to a degree which might already be seen as ‘overdressing’.

It’s obviously true that there is a fine dividing line between what is ‘overdressing’ and what is not, and this is clearly different from culture to culture, from society to society — the more male-dominated and conservative the society, the less ‘overdressing’ will be taken as ‘hyperfemininity’, but merely as an ‘acceptable look’ for women. The more open, tolerant, and equalitarian a society, the more it will frown upon women who wear lipstick during daytime, and the slightest detail may already be seen as ‘showing off’. No, it doesn’t automatically mean that women ought to wear Mao suits in order to hide their femininity — that would be going exactly in the wrong direction, as we can see in radical Islamist countries in the Arabian peninsula — but it means that ‘dressing up’ is reserved for very special social occasions, and it is expected that women, in their daily chores (unless they have a strict dress code at work), dress casually, and, more importantly, naturally. And yes, that means no makeup, no complex hair styles, no shapewear, no overly high heels, and so forth.

It’s important not to generalise. Of course many women love to ‘dress up’ and they do it for themselves (and not to attract potential sexual partners, or to ‘conform’ to the male-dominated society which imposes them a self-objectification), even on the most equalitarian and tolerant societies — after all, being tolerant also means allowing women to dress as they want. What I’m talking about is only about averages. It’s safe to say that the average woman does not ‘overdress’ in public, except on special occasions (and, of course, what ‘overdressing’ means will also depend on each society and culture). She does not feel to be a ‘lesser woman’ because of that. Rather the contrary: if she has at least been in touch with feminist thought, she will actually feel empowerment by having the choice not to overdress; and, conversely, she will frown upon those that overdress as being ‘weak’ and ‘frail’ because they are still unable to break free from the male-imposed stereotypes. Well, at least some of them will think that way (my wife certainly does — and she is by no means the only cisgender woman I know who thinks exactly like that).

This, naturally, reinforces the claims made by cisgender feminists. Because transgender women so often need to overdress — even if it’s just slightly — as a survival strategy (see Sophie Labelle’s comic), it means that, from the perspective of an outsider, it’s their body and appearance that validates their femininity. Remove the garments, the shapewear, the makeup — and, in some degree, the hormones — and that person will reveal themselves as the (biological) male they have been born as. You can see how the argument is not so silly or stupid after all. Radical feminists might be politically incorrect, but they are not completely and utterly stupid. They do have a point here. It might be a weak point, but it’s still a point.

As Sophie Labelle points out so clearly, it’s because we have not overcome gender stereotypes that transgender women are pushed into ‘overdressing’ (or, if you wish, into taking hormones and having surgery) to be able to be socially validated as ‘women’. Here, naturally, from my perspective at least, is where radical feminists get it all wrong. We transgender women are more to be pitied than censored; in other words, hooray for cisgender women, who can validate their femininity without any kind of exterior changes — they can just be themselves, more power to you, oh happy happy joy joy, we are so excited to live in a time and place where this is actually true for cisgender women. But have mercy on us transgender women (or at least show some compassion): we have no other choice to validate our femininity. At least most of us have not been blessed with perfect androgynous bodies. So we have no choice but to try to ‘fit’ by using all tricks of the trade (which, by the way, were originally designed for cisgender women, of course, and they naturally use those tricks as well during those special social occasions when they are still expected to look gorgeous) — even if that means, technically speaking, that we overdress to validate our femininity. Tough on us.

But it’s not true to say the contrary: because transgender women (often) cannot be validated by society as women, without at least some ‘dressing up’ (even if it’s very subtle), then they are not women at all. No. It doesn’t work that way. You cannot ‘see’ what we call the ‘inner female core’ — which expresses itself not in the way one dresses, but in the way one feels, and, as a consequence, acts, behaves, interacts with others, adopts a social role, and so forth. Cisgender women have been blessed by Nature to have the right combination of genes and chemical reactions which naturally give them a body that validates their ‘inner female core’, and that’s all what they need, nothing more. Most transgender women, unfortunately, were not so lucky. That’s the only difference between cisgender and transgender women: the luck in having the right genes that match their ‘inner female core’. Cisgender women are lucky; we transgender women are not. And it’s very unfair for radical feminists to somehow blame transgender women for having been born with the wrong genes — as if we had any choice in that!