If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.

You all know this classic example of inductive reasoning: based on a series of observed characteristics, we assume the most plausible explanation for them (the simplest theory that fits the facts), even if sometimes… we are wrong (for instance, a mallard looks, swims, and quacks like a duck but it is no duck — still, we would be right most of the time, and that’s the whole point.

MtF transexuals will obviously argue the same way: if it looks like a woman, walks like a woman, and talks like a woman, well, then it probably is a woman. Indeed, we would also be right most of the time, but… perhaps not always.

What, quoting Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists??

These days, science (both medical science and social science) agrees with a fundamental tenet of transgenderism: only the person herself or himself knows what their gender identity is. We can provide guidance in the sense of helping one’s self-discovery, but, ultimately, your gender identity is something only you can know, since we really cannot read minds…

While legally this might not be the case (few countries as such allow self-determining gender identity – my own country only started to allow that on April 6), doctors these days, at least in more liberal countries, will assess one’s gender identity based on what that person tells about themselves. And doctors will also use inductive reasoning: based on a lot of questions, they can, with reasonable accuracy, give a diagnostic of one’s gender identity. This is was ultimately they will report to allow that person to transition.

Now, Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists could not care less about scientific facts (do they remember you of someone?… all right, let’s skip US politics for now 🙂 ). Although their logic is rather convoluted (and I’m being very nice in classifying their argumentation as ‘logical’), the end result is that TERFs assume that only TERFs are able to tell if someone is a woman or not: it’s a question of peer recognition. And TERFs, as you know, do not accept people assigned male at birth as ever being ‘women’. Instead, they see them as very dangerous incursions into their territory, namely, patriarchy agents ‘disguised’ as ‘women’ who are redefining what a ‘woman’ is supposed to be, and therefore perpetuating the patriarchy (as opposed to believing that most trans women, when they are feminists, are actually abandoning their privilege as members of the patriarchy, just because they do not identify with them in the least — and that’s something TERFs pretend not to see), by establishing the ‘rules’ of who should be considered a woman and who should not. In other words: TERFs do not recognise trans women the ‘right’ to call themselves ‘women’ at all, much less to ‘define’ what a ‘woman’ is supposed to be; that’s a privilege only TERFs have, and it’s non-negotiable. That summarises pretty much their argumentation.

Now, we can simply ignore TERFs (like we ignored certain tall people with strange hair and small hands… ok, ok, I promised not to go into US politics, so I won’t!), brush them off, label them as insane, and go on with our lives. After all, we know exactly what a ‘woman’ is supposed to be, right?

Strangely enough… the answer is not a loud ‘yes’. As a matter of fact, one of the many criteria for transexuality is to ‘consider oneself to have the feelings and emotions of a gender different from the one assigned at birth’. If a sexologist, therefore, asks a trans woman how she feels, she will tell him that she feels like a woman, has the emotions of a woman, and none of the stereotypical feelings/emotions/thoughts of a man. Affirming this is something that goes a long way towards the diagnosis.

TERFs, by contrast, ask ‘how do they know?’ In other words: a trans woman will have been born with a male body (or at least a body that is more male than female). That body will have produced male hormones (either only in the womb, if that person’s transgenderity is caught very early; or during puberty, if the person only seeks transition after adolescence), which will have changed the chemical composition of the body, and turned it into ‘male’ (giving them primary sexual characteristics in the womb, and secondary ones during puberty). While we cannot affirm how exactly the brain was affected (and in the case of trans people, the brain — and the mind emerging from that brain — does not seem to be affected whatsoever by the hormonal cocktail which changes the body), TERFs assume that, for all purposes, a trans woman cannot feel what a cisgender woman feels, because they don’t even have the right body to ‘feel’ things properly.

There is here a strong fallacy — TERFs who are less experienced in logic will argue that trans women do not have an uterus, and, as such, they cannot feel what a ‘real’ woman feels.

This, of course, is stupid; first of all, there are many women without an uterus. Either they have been born with a genetic defect which prevented their uterus to fully develop (but they have normal hormonal levels and therefore fully develop as females, and identify as such), or they might have been forced to remove the uterus due to disease or cancer. They are not ‘lesser’ women because of that. On the flip side of the coin, uterus transplants are now a reality, although they are still at the experimental stage; and, once they become a routine surgery, due to the difficulty of obtaining potential donors, it’s unlikely that they will be available to trans women ‘soon’. However, that’s hardly the point: the question is that all attempts to define ‘women’ based on whatever physical attributes one might choose will utterly fail, since eventually there will be some woman lacking characteristic X and still be called a woman; while there will be some male person with precisely that characteristic X and still be considered male.

But even when we move towards mental states, the situation is hardly simpler. We know now that males and females of the human species have exactly the same brain capabilities – and that includes intelligence and emotional intelligence as well. One way we can see stereotypes being so easily broken is by looking at how women complete their university studies in astrophysics, engineering, or any other degree requiring a lot of complex math – contradicting the stereotype that ‘women are not good at math’ – or they become world-famous architects, also contradicting the theory that women are not good at spatial reasoning; and remember that in these areas the number of new degrees comes from women, not men, something which is true across Europe and North America (but also on some countries where women were traditionally not allowed to study and who have recently given access to all high education degrees – here, they outnumber men as well). On the other hand, the top chefs in the world are mostly male, and so are most of the best fashion designers – saying that men are not good at cooking or sewing is simply stereotyping again.

When we start talking about emotions, and about how women are good at intuitive thinking, while men are more rational… well, if we are serious about doing a non-biased study, we will (not surprisingly) find out that both intuition and logic are equally used by men and women; giving an average group of men and/or women, there will be some who are more intuitive, some who are more rational, and this is not really something that either gender is ‘better’ at doing. Similarly, the issue about ’emotions’ or ‘feelings’ is also not shifted more towards women than men; it’s just that socially each is conditioned to express themselves differently. Anyone who has watched a football game knows how deeply and intensely run men’s emotions!

So the ‘deep thinkers’ among TERFs (yes, there are a few…) present a much more convoluted reasoning: to be a woman one has to have been raised as a girl since childbirth, going through puberty as a girl, and finally become a mother and a wife, or at least aspiring to put their uterus to good use. Essentially, therefore, being a woman is basically getting the whole female life experience. And this is something that late on-set MtF transexuals obviously cannot have had.

The problem for TERFs is that these days trans children are being identified as such at such an early stage that they will practically get the whole experience, at least since the moment they are conscious of their own selves – and ultimately that’s what counts! So I wonder how they argue these days (to be honest, I don’t really keep up with their ranting…). Still, it’s clear that TERFs do not agree that anyone is allowed to decide who is a woman and who is not — except for TERFs, of course. And on the reverse side we cannot even create a list of characteristics that ultimately decides who is a woman and who is not, at least if we work from a neutral point of view.

The issue is exactly that: we do not start from a ‘neutral’ point of view. Instead, we make our assertions based on social roles – constructs that serve as archetypes for each person to identify with. Thus, girls will have a predisposition to be with other girls and learn from them what it means to be a girl – in that particular society. This will show as specific mental traits (including how one’s personality is shaped) – say, women are ‘allowed’ to weep in public when they are angry or sad or disappointed, while men are only ‘allowed’ to do so when their soccer team loses. These are all acquired behaviours which will change from society to society, and from epoch to epoch; men in the 18th century wore makeup just as women did, and their clothes were as complex and colourful as the dresses women wore; furthermore, they had no restrictions to fully express all their range of emotions in public. It used to be women who were told not to express themselves publicly, to remain silent and submissive; the 18th century allowed both genders to fully express themselves; and from the 19th century onwards, both genders became much more controlled about the display of their emotions. So we will always need to take into account a specific social environment when talking about the gender role differences. They are not obvious, much less intrinsic or inborn; the only thing which is, indeed, defined at birth is the identification with a specific gender, and that does indeed mean that boys want to become men (following the archetypes and stereotypes that are current in their society) and girls want to become women.

And here is where the catch is: a semantics issue, where we confuse ‘being a woman’ in the biological sense and ‘being a woman’ in the social sense. We really need to be clear about what we’re talking about!

TERFs claim that trans women, no matter what they do to their bodies, will never ‘become women’ (according to whatever biological/behaviourist definition they might come up with). That’s only true in the strictly biological sense – but not in the sense that matters, that is, in one’s gender role.

Ok, so let’s delve deep into human biology…

It’s not unusual to question what exactly defines a ‘woman’ or a ‘man’ in our contemporary society: after all, philosophers (and feminists!) do it all the time. It used to be simple: you’d look at the genitals and say, this person is a man, this is a woman, this is something else (on those societies that allowed third genders) or an Abomination Unto the Lord and should be killed/maimed (as we did until very recently in the West). There was no question of allowing women with male genitalia or vice-versa, even if history — from Joan D’Arc to le Chevalier D’Éon — is full of exactly those examples. Still, we can at least agree that such varieties from the norm were unusual; they were (and still are!) considerably rare.

But ‘rarity’ is not something that can used as a pretext to ignore its existence. For instance: people are constantly confusing the ‘flu with the common cold. The common cold, as its name implies, is common: one in every five persons in the world will contract it at least once this winter. The ‘flu, by contrast, is relatively rare: only one in 1,500 or so people will be affected by the ‘flu. We still continue to confuse both, and believe that an extra-tough case of the common cold (‘rhinopharyngitis’, as doctors call it to make it sound more serious) is a ‘flu, when it’s absolutely nothing of the kind: the influenza virus (causing ‘flu) has nothing to do with the rhinovirus (causing cold). They are different kinds of viruses. It’s just that they cause similar symptoms, but a lot of diseases cause symptoms that (at least at the beginning) are very similar to the common cold. And to make things even more confusing, both the ‘flu and the common cold are often confused with a form of rhinitis (there are many!) which might not even be triggered by any microorganism at all, but just be an allergic reaction to the change of weather. And don’t forget hay fever — which happens by the end of summer — which is also an allergy which also shares symptoms with the common cold. In other words: except for someone with a little bit of observation powers (or a trained doctor!), all these diseases seem to be one and the same, although they’re not — they may be not even related at all, they just cause similar (but not the same) symptoms. And this leads to all kinds of silly superstitions — like, for instance, that the cold ’causes’ the ‘flu (it doesn’t; the cold usually affects negatively all microorganisms; it’s just that in the cold season our immune system may be weakened, and therefore we are more likely to contract diseases), while in truth the cold can only ’cause’ one form of rhinitis, at worst, and you must be prone to allergies in the first place. Similarly, someone with a rhinitis or hay fever cannot infect anyone, no matter how much they are sneezing, coughing, and leaving bits of snot around, because allergies cannot be ‘caught’; while you just need to be in the same room as someone with the ‘flu to catch it (they don’t need to cough or sneeze, just to exhale), because that’s how virulent the influenza virus is.

So, enough about sneezing and coughing! The analogy, I hope, is not lost upon you: when we talk about gender identity and gender expression, we tend to confuse a lot of issues, because there is a lot of misinformation, superstition, and plain old prejudice. Sometimes, as I nastily like to add, there is some jealousy — because of the superstitious belief that anyone outside the heteronormative binary gender has way more sex (and in incredibly more satisfying ways!) than those who stick with the God-given sexuality and gender, there is some resentment from the religious folks out there — they wished they could have much more interesting sex lives, but they aren’t allowed to have them, so, full of hate towards those who they believe to be sexually much more liberal, they lash against them. All right, so this is not an established scientific fact, but just something I came to realize over the decades — which baffled me at the beginning. It’s a superstition tracing back to the concept that there is only one ‘approved’ way to have sex, and that’s to procreate — anything else ought to be repressed. One would believe that such a backwards, superstitious idea would have been rooted out of our societies centuries ago, but no: it persists. Just like the superstitions around the ‘flu persist, in spite of decades of medical science telling us what each type of disease is, and how to distinguish their symptoms.

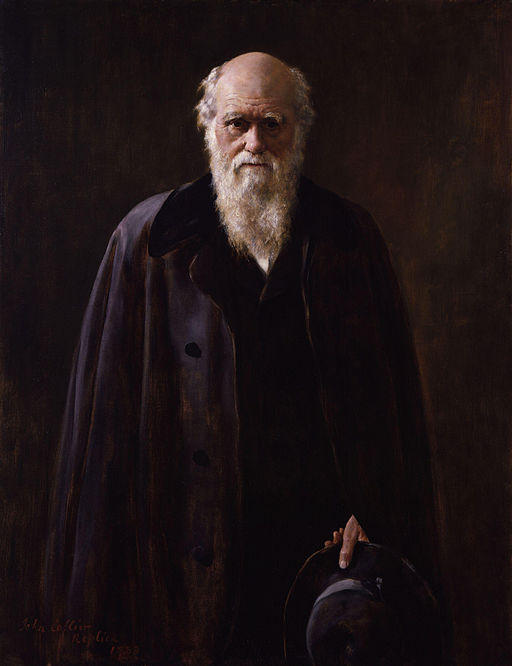

It’s also curious that, in the West at least, gender variance and sexual orientation have not been given much thought before the 19th century. It was assumed that it existed, but people simply didn’t talk much about it, they didn’t write about it, they didn’t draw complex theories about it. Men in the 18th century were simultaneously rascals and effeminate; ‘effeminacy’ was an affectation of the aristocracy (who could indulge in such pleasures as having lots of costly clothes and wearing makeup and wigs all day); this hardly had anything to do with gender stereotypes or sexuality stereotypes, but, eventually, by the time of the French revolution, things started to change, the concept of the ‘gentlemen’ was born (someone who was not a rascal and was guided by a much narrower moral compass), which in turn launched the West in an era of puritan thought, culminating perhaps with the Freudian notions that everything that was wrong with our minds was rooted in sexual issues. In retrospective, we could blame Freud for pretty much scientifically endorsing the notion that ‘sexual perversity’ is rampant in our societies and that all mental issues we have are somehow related to deviant sexual behaviour. Over a century later, we are still stuck to Victorian prejudice, both from a religious standpoint, but also a ‘scientific’ one, by pointing our finger at Freud.

Now, the mere fact that sexuality started to get studied and researched in a methodological fashion in Freud’s days is a good sign; even if Freud got lots of things so wrong, at least he encouraged generations of scientific thinkers to analyse gender and sexuality — formerly taboo areas of research! — more closely, and start to describe them scientifically. The 20th century helped things further, thanks to new advances like medical imageology (yay for X-Rays — you could observe how a human being worked from the inside without killing them first and dissecating them!), genetics (so that’s what determines how a human being will develop!), or very sophisticated medical drugs like synthetic hormones. Still, it was only around the 1950s that the first so-called sexologists were starting to seriously abandon their former prejudices, at the light of new discoveries which simply failed to fit into decade-old assumptions.

What we know now is unfortunately not yet mainstream knowledge; in other words, it hasn’t trickled down to the school’s classroom when students open up their biology books and study human anatomy. We are still stuck in explaining the differences between male and female bodies; it is assumed in the classroom that male humans behave as ‘men’ socially, while female humans behave as ‘women’. Literature, among other subjects, will focus on how males and females interact socially, and how this interaction changed over the centuries; similar comparisons might also be found in geography (showing how gender roles change across continents), history (where the change is seen across time), or even philosophy (where some attempts have been made to ‘explain’ why men have male gender roles and why women have female ones, and why some explanations inherited from the ancient philosophers may not make any sense today). However, this is still not enough: students only learn about the cisgender heteronormative view. Schools having sexual education in their curricula may talk about differing sexualities (because at least one in ten persons will not be heterosexual), but that’s the only thing which is given the thought of ‘variance’. Transgenderity might never be a word heard in school (it certainly wasn’t in my days; and even homosexuality was never mentioned by teachers, at least not during lectures in class). The idea that biological sex is different from sexual/romantic attractions which is not the same thing as gender identity and has nothing to do with gender expression is simply never taught in school. The main reason for that, I think, is that even progressive, liberal thinkers believe that teenagers are already so much confused about their own sexuality that it is pointless to explain things in full.

By doing so, however, we are still bound to the idea that biological conditions somehow influence everything at the same time — and while this is certainly the case for a majority of people (or at least that’s what those people will tell about themselves), we also know, from a scientific point of view, that things are not that easy.

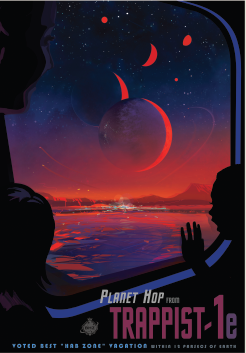

An interesting concept which I have heard from scientists Jack Cohen and Ian Stewart is lies-to-children. This is basically telling a gross oversimplification of a very complex issue to children (or laypersons) that can be used as a teaching tool, but which is fundamentally wrong.  I like the simple example of explaining people why the Earth orbits the Sun, so that they understand why it’s not the other way round, as we experience it when looking at the way the Sun moves across the sky. But ‘the Earth orbits the Sun’ is an oversimplification — in reality, both turn around a common point which is the equilibrium between the mutual gravitic attraction of Earth and Sun. Because this point is pretty much deep inside the core of the Sun, it makes little difference, for a layperson, to know about the difference. But it is thanks to this tiny difference that we have managed to figure out hundreds of extrasolar planets: because these also slightly influence the movement of their stars, making them wobble just a tiny bit in their paths, and we can measure that wobbling and figure out how many planets (and how big they are) are orbiting that particular star. In other words: if we took that oversimplification literally (‘no, I’m sure that’s what I have been taught at school!’), then we would never have found those amazing seven Earth-like extrasolar planets in a red star in our stellar neighbourhood.

I like the simple example of explaining people why the Earth orbits the Sun, so that they understand why it’s not the other way round, as we experience it when looking at the way the Sun moves across the sky. But ‘the Earth orbits the Sun’ is an oversimplification — in reality, both turn around a common point which is the equilibrium between the mutual gravitic attraction of Earth and Sun. Because this point is pretty much deep inside the core of the Sun, it makes little difference, for a layperson, to know about the difference. But it is thanks to this tiny difference that we have managed to figure out hundreds of extrasolar planets: because these also slightly influence the movement of their stars, making them wobble just a tiny bit in their paths, and we can measure that wobbling and figure out how many planets (and how big they are) are orbiting that particular star. In other words: if we took that oversimplification literally (‘no, I’m sure that’s what I have been taught at school!’), then we would never have found those amazing seven Earth-like extrasolar planets in a red star in our stellar neighbourhood.

Similarly, when children learn in school about the differences between the two genders of the homo sapiens species, they get presented a lie-to-children: a simplified theory that humans with XY chromosomes are male, while those with XX chromosomes are female, and we distinguish them through different embryonal development (different primary sexual attributes, e.g. a penis for the boys, a vulva for the girls) and different maturation through puberty (acquisition of secondary sexual attributes). This leads to the widespread belief that ‘men are men, women are women’ so commonly found among religious fundamentalists, conservatives, and other narrow-minded groups (including TERFs!) — because that’s what people get taught at school. It’s amazing the amount of comments you can find on the Internet coming from highly intelligent and educated adults who will stick to these definitions of the sexual differentiation among humans, who, even in spite of having the ability to educate themselves further on the subject, and having rejected many similar lies-to-children during their professional career, refuse to do so regarding how the human sexual development is anything as simple as what we get taught at school. What surprised me most is when doctors repeat these lies-to-children, fully believing them to be literally correct.

In practice, things are much, much more complex than that.

One of the best descriptions I have read about how (biological) sex is determined in humans (unfortunately I didn’t save the link, so you have to google for it yourself) is that our bodies are in a so-called sexual hormonal unstable equilibrium. It sounds scary, but this theory has great explanatory power, and is therefore worth considering as a good description of reality (as opposed as just a more sophisticated form of lies-to-children).

Basically, what happens when we’re first subject to sexual hormones, still in the womb and a long time before there is any resemblance to anything ‘human’ in our embryo, is that our genes encode instructions to produce both male and female hormones — this is, by the way, the reason why most people will always have both kinds of hormones. In a sense, the labeling of ‘male’ and ‘female’ at this stage is purely arbitrary: the body will develop proto-genitalia which are undifferentiated (in other words, no matter what chromosomes you might have, you will start your life with some genitalia which are technically neither male nor female). Don’t worry if this sounds queasy; at that stage, you will still have a tail, so having undifferentiated genitalia is really nothing extraordinary compared to all the other strange body appendages we go through as embryos. Also note that this knowledge is not recent; as far back as (at least) 1858, Gray’s Anatomy already had drawings of these stages of development — you can see for yourself how closely the male and female sexual organs look like during the embryonal stage. It should also not come as a surprise to you that both kinds of sexual organs mostly share the same tissue, they just followed different development paths. In other words, there is much less difference in terms of equivalent functionality (biologists call it homology) than many people still believe (ironically, during the Victorian Era, it was believed that women did not even feel sexual arousement just as men did, even though they knew very well how those homologous structures developed — that is, they ought to have a good understanding on how things worked, since they knew quite well how the sexual organs had developed, i.e. which parts ended up at each position).

Now, what current research shows is that the differentiation comes mostly from a delicate balance, or equilibrium, between the sexual hormones. To be more precise, biological males have one unstable equilibrium, where male sexual hormones (androgens) predominate, while biological females have a different unstable equilibrium where female sexual hormones (estrogens) predominate (and I’m oversimplifying again — there are a lot more hormones influencing the sexual development, but this can easily get very complicated, so bear with my ‘more advanced’ lies-to-children, while at the same time reminding yourself that this is just a part of the whole picture). This equilibrium is not ‘fixed’ for the human species, but is rather specific to each individual, and it is influenced by a lot of possible reasons — one of which, for instance, is the amount of androgen and estrogen receptors to which the hormones can bind to, and how well these receptors work.

In other words: to produce a ‘normal’ male human (‘normal’, as always in my articles, is a mathematical term simply pointing to a statistical majority), there has to be a certain amount of androgens that need to be synthesized by the body; such androgens must be, to a high degree, functional (i.e. the genes encoding the information for that sexual hormone cannot have been subject to a mutation which renders the resulting androgen non-functional — in this oversimplified explanation, ‘functional’ means ‘the ability to connect to androgen receptors’); and the body must have produced a high number of androgen receptors, to which androgen can connect, and, therefore, start to influence the sexual development of that individual into a specific direction. But at the same time the body must also keep the production of estrogens at a low level, as well as the number of estrogen receptors. Males do produce estrogen, and they do have estrogen receptors, because there are certain body functions which rely upon these sexual hormones — not all of which are related to ‘sex’ (even though, perhaps surprisingly, the increase of libido in males requires not only testosterone but also estrogen; just having testosterone is not enough!), namely, things like protecting the arteries to prevent cardiovascular disease (and this is one of the reasons why women are much less prone to die from heart attacks than men — they’re better protected, since they have more estrogen circulating in their blood stream), but also play a role in regulating the bone structure and even brain functions like verbal memory… so, yes, healthy males need estrogen as well, and this is why both males and females have both androgen and estrogen receptors. This point is crucial for the explanation later, so make sure you remember it!

Again, the lie-to-children that ‘women have female sexual hormones, men have male sexual hormones’ is nowhere close to reality. Both genders have (and must have!) both kinds of hormones. Or else… kaput. They die. Humans (and, in fact, most vertebrates and many insects) cannot survive without both kinds of sexual hormones, and both need to be present at a certain level — during all our lives. Indeed, one of the reasons of our decline in advanced age is that we simply don’t produce enough sexual hormones of either kind, and that means the body will slowly lose the ability to protect itself from many diseases. It would be nice to say that getting hormone therapy during all your life would prolong it indefinitely, but, again, things are way more complex than that, although it’s true that having hormone therapy at an advanced age can at least make some age-related diseases more tolerable. The only reason why we don’t do this routinely (although it’s becoming more and more popular to ‘treat’ menopause with hormone therapy) is mostly because the effects of such therapies have not been studied enough except on transexuals; and, secondarily, because of a certain morality that induces conservative doctors to believe that ‘sexual hormones’, i.e. hormones that are required during sex, should not be given to old people, since we still expect them not to have a sexual life any more — which is just a form of prejudice against old people, a kind of ‘ageism’, where we somehow expect ‘senior citizens’ to resign themselves to a life full of pain, diseases, and no more sex. But… I digress!

It’s worth mentioning what exactly those androgen and estrogen receptors are. Basically, they are very complex proteins, which will activate certain genes (which will produce, in turn, other proteins) when androgen or estrogen binds to them. They are different; there is one androgen receptor but at least two estrogen receptors, encoded by different genes. What happens exactly when androgen connects to an androgen receptor, or estrogen connects to one of the types of estrogen receptors? Now, a full description is waaaay beyond my own understanding, but I can give you another sophisticated lie-to-children. First, however, you must understand a little bit about how DNA works. And yes, this will be a gross oversimplification and incorrect in many aspects; after all, I’m not a genetics engineer, nor a molecular biologist, much less a doctor; so take it with a pinch of salt, and look it up at least on Wikipedia, if you’re really interested in the nitty-gritty details.

The common lie-to-children is that DNA is sort of a ‘blueprint’ which produces the proteins required for a human body (well, any living species, actually). So basically the idea you get at school is that you start reading DNA from the beginning to the end, and, hey presto! you get a human being. And you might also have an idea that during this process, some genes might have defects (mutations), and these will produce all sorts of terrible diseases.

A more thorough explanation will also say that the major reason for those mutations to produce those diseases is not necessarily because there is something ‘missing’ from the protein (because of a ‘wrong’ gene at a certain location). Unfortunately, things are so complex that proteins are not merely an assembly of aminoacids; they need to be ‘folded’ in a certain way, in other words, the 3D structure of the protein is crucial for its specific function. This is a long shot from learning, at school, basic chemistry (like oxidation and reduction processes), where you basically couldn’t care less how a molecule of H2O looked like in 3D.

When dealing with living beings, however, the structure is incredibly more fundamental, especially when we’re talking about mechanisms which will activate other mechanisms… let me try to explain it differently, and get back to what a hormone receptor actually does.

So, no, DNA is not like a computer programme which you start at the beginning and stop at the end. Rather, what happens is that an insane amount of highly complex molecules determine where you start to read and where you stop. These molecules, in turn, get ‘activated’ for different reasons, almost all of them triggered by a certain amount of chemicals present in the body. A typical example from a different scenario: your body cells require sugar (glucose) as a form of energy to do their work. When you eat carbohydrates, where the glucose comes from, your body needs to tell the cells to allow that glucose to be absorbed — as much as necessary, but not more than necessary. This is done by triggering the production of the hormone insulin in the pancreas: in other words, the concentration of sugar in the blood will trigger certain complex proteins to tell the insulin-producing cells to start reading the gene for producing insulin (I’ll skip the fascinating way how this actually works, I’d take the whole day to do that, but read it up, it’s really astonishing). Insulin, in turn, has a specific 3D structure which acts as a ‘key’ to insulin receptors on each cell; when the ‘key’ connects to the ‘lock’, the cell becomes porous to glucose (i.e. it allows glucose molecules to flow in). When ‘enough’ glucose enters the cells, insulin ‘shuts down’ the glucose gates, meaning that no more glucose is allowed to enter the cells. If there is still enough glucose around, however, the body needs to get rid of the excess — again, insulin (which is still around!) will this time tell the liver to store the extra glucose. As sugar levels in the blood drop, the special molecules in the pancreas insulin-producing cells stop being ‘active’, and that means they will also stop producing more insulin from reading the gene in the DNA that describes how insulin is assembled from aminoacids. The excess insulin will eventually be flushed out or reabsorbed/recycled (I’m unsure of exactly what happens to insulin, but its levels in the body will drop). When the cells require more energy, after using up all the glucose, they will trigger a very complex chain of chemical events that ultimately will trigger some higher mental functions in the brain letting you know that you’re hungry and are supposed to eat again.

You can see how things can go wrong even with such a simple mechanism. For example, the gene producing insulin may have a mutation, and now the body can only produce a insulin-like hormone which, however, has the wrong shape (because it has a different sequence of aminoacids, it will ‘fold’ differently) to act as a ‘key’. In other words: everything is in place, ready to get all this complex system working, but unfortunately, the key that fits into the lock that allows glucose to enter the cells is broken. This is a simplified explanation of type 1 diabetes — meaning that people with type 1 diabetes will require all their lives to get extra insulin, since their own body only produces defective insulin. Thankfully, because all the rest of the mechanism is in place, the extra shots of insulin will trigger everything in the correct order so that you can trigger all required mechanisms to keep both the sugar levels in the blood, the liver, all the cells — as well as the insulin levels required to maintain all of that.

Another possibility is that the ‘lock’ is ‘broken’. This happens, for instance, if you are repeatedly using the ‘key’ over and over again; eventually, the ‘locks’ start to break apart, and, at some point, the ‘key’ does not fit any more. In slightly more technical terms: the insulin receptors start to become less sensitive to insulin. In some cases, they can even become resistant to insulin (i.e. reject insulin completely and refuse to allow the insulin protein to ‘connect’ to it). This is pretty much a description of type 2 diabetes: due to a lifestyle including a wrong diet, those nasty insulin receptors work much worse than before, and there is nothing else that you can do but to ‘overload’ them with insulin, in the hope that at least some of them will react. And, yes, changing your lifestyle and diet will have an effect — those lazy receptors might start to work again as they should, or possibly the new cells that get produced as you change your lifestyle will have perfectly working receptors.

Confused? Overwhelmed? You well might be. And remember, the ‘insulin cycle’ is one of the simplest, and that’s mostly because there is a single gene for coding insulin, and the mechanism how the sugar blood levels are kept in check with more or less amounts of circulating insulin is rather well understood.

Now we can turn back to sexual hormones. The principles are the same — through release of certain chemicals, driven by sexual hormones attaching to specific receptors, and therefore pushing the protein-producing factories (the ribosomes in the cells) to synthesise certain proteins encoded in the DNA, a typical development is achieved — either in the direction of producing male sexual characteristics or female ones. But the complexity is several orders of magnitude higher than with the insulin-sugar balance — we are talking not only about several different sexual hormones, but receptors which activate a whole complex chain of events, triggering the production of more proteins, which in turn will activate more genes, and produce different proteins, which in turn will also affect the levels of sexual hormones in the body… and so on. You can start to appreciate the complexity just by twisting your mind around this description! And remember, I’m still oversimplifying — bringing it down to the level that I can understand (I’ve just got a smattering of chemistry in my curriculum, but I know almost nothing about complex molecular biology!). Reality is way, way more complex than this. You can also start to understand that things can easily go wrong, among this complexity. And that’s where it begins to become interesting…!

So… if both genders produce both kinds of sexual hormones, how does the body prevent both from affecting the sexual development? In other words: if we all have the potential to get sexual hormones attached to receptors, and these, in turn, will regulate what proteins will be produced (related to either male sexual development or female sexual development), how does the body ‘know’ which way to go?

Clearly this mechanism is still a lie-to-children: it just explains half the story. So, the body not only needs to get the cycle of sexual hormone production in balance, according to one’s gender, but it also needs to prevent the opposite cycle to function. In other words: a male body needs to produce inhibitors of the ‘female’ development cycle while at the same time promoting the ‘male’ development cycle. This needs to be in perfect equilibrium during all the development time, or else this won’t work!

You now should be properly amazed that this works at all, most of the time. Well, remember, Nature has been experimenting with this for millions of generations — sexual development came relatively early in the history of life; even most modern plants have it — and Nature tends to retain things that work well for a long, long time, until something better comes along. But if some mechanism tends to provide excellent results, then, no matter how complex it may be, or how ‘old’ (in the sense of having been developed millions of generations ago) it is, it remains in our collective DNA for really a long time. This is fortunate from the perspective of genetic engineers and molecular biologists: the ‘assembly stones’ that we humans have are shared with millions of species. There is just one DNA. While it technically could encode an infinite number of proteins, in reality, a finite amount has survived the rigours of evolution, and we all share a lot of things in common. And by ‘we’ I’m speaking of the entire spectrum of life on Earth — from bacteria through plants to animals to humans. Of course, younger species (i.e. humans, for instance…) tend to have inherited a lot of baggage from ancient species and still use it, but have made it more and more complex.

Humans, for instance, have a very complex DNA encoding. One would assume that we humans, being a relatively young species, and carrying a lot of baggage and adding whatever genes are required to make us human, we would therefore have the highest amount of genes in exceedingly long DNA strands. Actually, the reverse is true: it’s strange, but we have less genes than more primitive species (‘primitive’ here in the sense of ‘less complex organisms’ — some of those species might actually be ‘young’, e.g. bacteria that affect humans are as ‘young’ as humans, or even younger, but a single-cell organism like a bacteria is necessarily several orders of magnitude less complex than a whole human being…). This baffled everyone for a while, until researchers found out that we use DNA more efficiently — in other words, the same gene (or rather the same group of genes) can encode different proteins, depending on the environment. What this means is that we’re not humans just because we have human DNA; or, if you wish, if one places a strand of human DNA inside a mouse, for example, we wouldn’t get a human rodent as a result. The DNA is not enough — you need the whole environment, all those loops of chemicals creating all sorts of unstable equilibriums, which will fundamentally determine what genes will be activated, which ones will remain dormant, which ones will be combined with others to produce different proteins, or eventually the same protein with a different shape, which, in turn, will also affect the environment. Think of an automated traffic control system for a very large city: as traffic flows from one part of the city to the other — which will depend on the time of the day (e.g. rush hour or not) — all those traffic lights will need to go green or red to keep the traffic flowing, and that means they will have to be turned on and off at different rhythms. When a special event occurs — say, a soccer game at one part of the city — traffic will be completely different, and that needs rerouting, turning traffic lights on and off at other rhythms, which in turn will make traffic change, and that change will also be reflected on the way the traffic lights move from green to red and back. So you can see what is happening: the traffic lights shape the traffic, which, in turn, shape the way the traffic lights have to be turned on and off. Those two things are mutually influencing themselves.

Almost all living beings work like that as well — the chemicals in the environment dictate what proteins get produced from certain areas in the DNA, which, in turn, will also affect the environment, and, therefore, trigger other protein-building mechanisms from other areas of the DNA, and so forth. Keeping those cycles and loops in check so that there is an equilibrium is a tremendously complex task where gazillions of things can go wrong.

Let’s see a simple example. Suppose that you have been born with XY chromosomes. You would therefore expect that the body will attempt to produce androgen and enter the ‘male development’ cycle, while at the same time it will need to prevent that there is too much estrogen around to trigger the ‘female development’ cycle. This, in turn, requires all those receptors to be working well — in other words, the androgen receptors must bind to the androgen being produced, while the estrogen receptors must be mostly ‘turned off’ so that they cannot bind to estrogen (I said mostly because, as said, estrogen has other functions as well, besides sexual development).

But imagine that the gene that codes the androgen receptor is defective — in other words, it codes a protein that serves as androgen receptor, but, because maybe one or other aminoacids have been replaced due to a few wrong bases in the DNA, the resulting protein does not ‘fold’ correctly, and the result is an androgen receptor that is somehow ‘broken’ and fails to attach to androgen. Now we have a male organism producing lots of androgen (as well as some estrogen, of course) but all that androgen fails to trigger the male development cycle, because those androgen receptors are broken. The organism tries to compensate by producing more androgen receptors (as well as more androgen to connect to them), but it’s of no avail: all that extra androgen is sitting around, doing nothing. Worse than that: not only the androgen is useless to trigger the male development cycle… but because that cycle hasn’t been triggered… it means that the required chemicals that will ‘turn off’ the estrogen receptors have not been produced. In other words: there is a step in the ‘male development programme’ that is completely missing, the male development cycle has not started at all, and, therefore, the female development cycle cannot be blocked. What happens? Well, the estrogen will bind to the estrogen receptors, which are working as they should. More useless androgen is produced, but it does basically nothing; in the mean time, even the little estrogen that is produced starts triggering the female development cycle, because nothing is there to stop it. So the proteins that are being now produced are all related to the female development cycle: these, in turn, will trigger more and more areas of the DNA, where all required proteins for a female development are encoded, and the female development cycle starts in earnest.

But that’s not all. Remember, triggering one of those cycles means also blocking the other. So, even though this particular individual might have started with an androgen-estrogen ratio typically of a male individual, what happens now is that the female development cycle begins to block the male cycle. No matter how much androgen gets produced, now the female development cycle starts to inhibit its production — but since that androgen hadn’t any effect because it couldn’t bind to anything, and therefore could not affect the female development cycle, this now enters in full force — and its results are irreversible!

There is, however, a catch. Remember, this particular individual started with typical XY male chromosomes. Unfortunately for her, the bit that is missing on the Y chromosome has a lot of information related to developing the uterus, the ovaries, and much of what is necessary for the reproductive system to work. Thus, this individual will develop mostly as female, and, at birth, will have a fully functional vulva, and the doctors will say: ‘Congratulations, it’s a girl!’ because externally there is nothing that could give the doctors a clue.

And she will be a girl, because whatever influence the sexual hormones have on the brain (an area of much dispute, since the actual mechanism seems to be far more complex than what was thought — namely, that the brain structures for a male or a female are not directly associated to the sexual hormones, but to other molecules, also triggered by the female/male development cycle, which act directly on the brain cells, telling them to build specific proteins which will affect the way this individual thinks about their gender identity — the whole mechanism is still a mystery), this individual will be subject to whatever the female sexual hormones will do to her brain. Unsuspecting anything about their DNA, the child will clearly identify as female, recognise her body to be female, and because everybody else has not the slightest suspicion that she might be anything but female, will raise her as a girl — which is what she wants anyway.

There will be a few differences, though, but because human beings are so diverse, it’s hardly likely that anyone will notice them. Remember, this individual will not react to any androgen whatsoever. That means that her development will in fact be ultra-feminine — there will be no effects from androgen. And yes, at puberty this will mean big, round breasts, wonderful skin, no facial or body hair, but just luxurious hair on the scalp, and so forth… On the other hand, even if this person has no working androgen receptors, she still has parts of the ‘blueprint’ for a male; so, when things like the ‘growth’ cycle is triggered, because she has genes for a male growth, she will be usually taller than the average female in her area, with stronger bones, nicer legs… well, some have maliciously described them as ‘superwomen‘.

This is a condition known as complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) — a not-so-unusual genetic disease (which affects something between 1 in 5,000 and 1 in 20,000 women, depending on the study) which has, in the past, been completely undiagnosed. Such people identify as female and have an external female body, with both primary and secondary female sexual characteristics — usually quite well developed, and often very attractively so. The only hint that something might be wrong will be at puberty when they fail to menstruate; and, of course, lacking an uterus, they will be infertile. In the past, however, because there are so many possible congenital diseases preventing women to carry children, CAIS was simply shrugged away as unimportant; people affected with CAIS usually lead normal, healthy lives; they can always marry and adopt children, of course. And because their infertility is usually just something they will tell to their husbands, nobody in the world will be able to suspect that there might be anything ‘wrong’ with them (in fact, their good looks, perfect skin, and statuesque body might just raise jealousy and envy from other women, and desire in most heterosexual males…).

With the advent of modern medical imageology, doctors could see that at least something was wrong with these women — i.e. they lacked an uterus, and their vagina, consequently, would just be a ‘pouch’ leading to nowhere. This at least allowed doctors, at puberty, to see that their uterus had totally failed to develop and tell them the bad news: that they would be unable to bear children. Because there are so many diseases affecting the reproductive system and rendering women infertile, once again, for decades, even with state-of-the-art technology, CAIS remained undiagnosed as such — people with CAIS would just be bundled together with hundreds of other potential diseases affecting uterus development.

It’s just with the advent of modern (and affordable) DNA sequencing that doctors saw that something was utterly wrong: persons with CAIS were genetically male. Now, this is important to underline, because, again, there are lots of genetic ‘defects’ or mutations, where either the X or the Y chromosome gets damaged, duplicated, cloned, whatever… and the result may be male, female or a mix (intersex). In those cases, die-hard fundamentalists could just have pity on the ‘poor women — yes, because they are genetically women, they just have bad genes’, and TERFs would still consider those people women, just unlucky women with bad genes.

But people with CAIS are another story. They are, for all genetic purposes, male. They are not ‘genetic women with mutations’ or ‘bad genes’. They are male from all possible definitions at the genetic level. Sure, they are males with one mutation at one particularly sensitive gene — the androgen receptor gene — but they are males nonetheless. In fact, there are dozens of different kinds of people clearly male (mentally and physically), identifying as male without any doubt, but who have their DNA in much worse condition than people suffering from CAIS, who might just have one bad gene and nothing else. Worse than that, many males with ‘bad genes’ might suffer from genes broken down due to new mutations, i.e. their condition is not inherited, but the DNA formed from the strands of their parents just mutated at some point and broke down (which is actually very rare; human DNA is not that prone to mutations; it’s just that, at 7 billion individuals, we are such a big species that statistically something has to go wrong once in a while — even with billion-to-one chances of something to go wrong means that seven individuals might have been the unlucky ones!).

CAIS is different: it’s often (70%) an inherited condition. The parents might not even know they are the carriers of a ‘bad gene’. The androgen receptor is in a gene contained in the X chromosome (yes, that sounds strange, but that’s how it works), and, because women have two X chromosomes, they will still have one ‘good’ AR gene on one of the chromosomes, while carrying the ‘bad’ gene on the other one. That means that female offspring will also have at least one good AR gene (from the father) and one bad one (from the mother); it’s a recessive condition. Even male offspring might be absolutely normal — they can get the ‘good’ X from the father or the ‘good’ X from the mother. It’s just when they get the ‘bad’ X from the mother that things go wrong.

The AR gene is one of those genes that is very easy to mutate: around 400 different mutations are currently known (which is an astonishingly large number!). Not all of them lead to a broken androgen receptor: many might just not work as well as they should (because they are ever so slightly differently ‘folded’ and therefore androgen doesn’t ‘stick’ to it as well as it should). And yes, you’ve guessed: a partially, but not totally broken AR will lead to all sorts of intersex conditions, from very mild forms (the person is physically and mentally male, but may fail to develop fully their secondary sexual characteristics, for instance) to more severe ones (the person might have ambiguous genitalia, and mentally identify as a female, for example).

CAIS is by no means the only condition leading to intersex individuals, or to produce women who are genetically male — there are a good handful of other complications and conditions — but it is one of the more interesting ones, especially for transgender people. People with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (and the more severe forms of AIS) are not male. They are, for all purposes — physical, mental, legal — female. They have always identified as female, and nobody has ever questioned them about their gender identity. Before genetic exams became widely available, people with CAIS would not even have a ‘diagnosis’ of their condition … they would just be unlucky, infertile women, like so many others who carry XX genes. But, unlike all other women, people with CAIS have, for all purposes, male DNA. It’s not just having XY chromosomes that makes DNA be ‘male’. It’s because they have a fully functional ‘male blueprint’ encoded in their genes. The trouble is that this ‘male blueprint’ cannot be ever activated (not even artificially so) because the androgen receptor is broken. The organism with a ‘broken’ AR has no choice but to do their best with whatever they can find inside their DNA, and that often means a very attractive, statuesque woman; but one could say that this is a ‘side-effect’ of having a defective AR, that is, most species (and most certainly humans) are positively biased toward being female as ‘default’, and ‘becoming male’ requires a special effort; if the organism fails to develop as male, it usually develops as female instead (but remember that we know from the multiple intersex conditions that things are not that easy!). In other words: from a geneticist’s point of view, a person with CAIS is a ‘broken male’ who has failed to develop as such, and it’s just by a biological coincidence that they developed as female instead.

From the society’s point of view (and, of course, from the perspective of the individual with CAIS), it’s the other way round: this person is legally, emotionally, mentally, and physically female. They just happen to have a very slight genetic defect (it’s just one gene, after all) which prevents them to bear children. But they are perfectly normal, healthy women otherwise. Well, perhaps they might even be especially attractive on top of everything, but that’s not relevant!

Of course, MtF transgender people such as myself are always fascinated with people with CAIS, for a very unfair reason: jealousy! After all, MtF transgender people have also been born with XY chromosomes and a ‘male blueprint’. They also identify as female. But because they have fully functional androgen receptors, their body unfortunately has developed as male instead — so they have to suffer from gender dysphoria, and undergo complex medical procedures and face the disapproval of the more conservative and fundamentalist members of society as they try to adapt their bodies to the gender they identify with. People with CAIS have no such problems. Granted, they will never bear children, but neither will MtF transgender people — they will have to rely on adoption if they wish to have families.

This jealousy, of course, is completely inappropriate and actually a form of discrimination; people with CAIS have, after all, a genetic disease — one that is incapacitating, in the sense that they will never be able to bear children. So it’s very unfair to be ‘jealous’ of them!

Nevertheless, from an activist’s point of view, CAIS proves the whole point — that genetics is totally irrelevant for gender identity. We can repeat lies-to-children saying that ‘XY chromosomes lead to men, XX chromosomes lead to women’, but that’s just an oversimplification. People with XY chromosomes and a broken AR will be women and nothing more than women, and they will be socially accepted as such, because their bodies and minds are fully female, and have never been anything but female. Genetics doesn’t play a role in either their identity or social role. And, on top of that, CAIS is not that rare, and this should also raise a few eyebrows.

If CAIS prevents an individual from reproducing themselves and pass their DNA along to the next generation, why haven’t they been weeded out by evolution?

We have to go one step back, and frame the whole question in a new context, that of evolution. After all, we’re not talking about a de novo mutation — that is, a new mutation that popped up unexpectedly for a specific individual, because that particular individual had one strand of DNA incorrectly copied. De novo mutations in humans (well, in most modern species, to be honest) are actually very, very rare. DNA, by itself, replicates correctly 99% of the time — but on advanced and complex species as homo sapiens, there are a lot of other mechanisms to get rid of the few errors that might pop up. For instance, we might have duplicate copies of the same genes, so that if one gene gets affected by a mutation and fails to produce the correct protein, the other one will still work. Or our organism may have means to identify a broken protein and ‘fix’ it so that it works again, even at the cost of producing less of those — that’s ok, because the body has means of ramping up production, due to the complex ways of sustaining an equilibrium. Or the organism might just have mutated copies of a gene in some cells but not in others (a condition known as genetic chimerism). I don’t know about all the possibilities of ‘fixing’ mutations, but I’m aware that there are really, really many of those, so that absolutely devastating mutations are incredibly rare. For example, there is also an equivalent estrogen insensitivity syndrome, which, as you might expect, will make an XX individual fail to develop fully as female. But because the estrogen receptor gene is located elsewhere, it cannot be inherited, since a XX individual with EIS is unable to reproduce themselves and pass the ‘bad’ gene along. So all mutations of the ER gene have to be de novo. And this is so rare, so rare, that currently there are just two reported cases of EIS in the whole world. That’s how resilient our DNA is against ‘bad’ mutations!

Still, because there are so many humans — after bacteria and ants, we’re at the top of the list of the species with the largest number of individuals — as said, even billion-to-one chances will happen once in a while. But it’s worth repeating that the problem with CAIS is that it is not that rare. In fact, the 1:20,000 ratio is based on reported conditions. Up until 1950, CAIS was not even known as such. Individuals with partial AIS — which is much rarer than CAIS — would show ambiguous genitalia, i.e. some form of intersexuality, and as a result they had been better studied: so the condition could be described, but the reasons for it were unknown. Remember, we just know how DNA looks like from 1955 onwards; it’s just by the 1970s that we started to understand how exactly AIS is triggered, and that it was actually quite common for people to suffer from complete AIS, but because their external appearance would be fully female, they would escape diagnosis completely.

For all practical purposes — and this naturally continues to be the case on less developed countries with limited access to highly advanced medical exams, such as DNA sequencing — a person with CAIS was just an infertile woman: the kind of auntie we all had in our families who never got married because she couldn’t give birth to her own children, and therefore was the kind, beloved aunt who helped her sisters to raise the kids. And here is the crucial evolutionary trait: because humans are a gregarious species with an extraordinarily complex society, we historically favour large families where kids are raised not only by the parents, but by the other members of the family as well — from uncles and aunts to grandparents and cousins. Evolutionarily speaking, this makes sense, because family members share genes (even if in a much lesser degree than a parent-offspring relationship), and protecting the genes of all members of the family means a higher degree of getting one’s own genes — albeit inherited through one’s siblings — to the next generation. This strategy, in fact, is typical of gregarious species, and gregarious species have therefore an evolutionary advantage over the others: they can raise children together and therefore increase the success rate of those children to survive, therefore carrying the genes of a pool of members towards the next generation. Such strategies have made gregarious species extremely efficient at surviving — just see the two examples I gave before, ants and humans, being among the species with the most number of members (of course, this is another oversimplification, as obviously several gregarious species might actually risk extinction due to dramatic changes of their habitats — think about lions and wolves, for instance).

What has been postulated is that these strange genetic and/or development conditions which emerge and are not so rare actually provide an evolutionary advantage as well. I’ve talked before about the current reasoning for the prevalence of homosexuality (and transexuality) in most species, especially on the gregarious ones which raise children together, is that such individuals, while not reproducing themselves directly, are able to aid their siblings (and other members of the family) to help them raise their children, instead of focusing on their own (because they don’t have any!). Therefore, an homosexual uncle helping to raise his brother’s children will enhance the rate of survival of their nephews — who also carry genetic material of the homosexual uncle, of course, just not as much as if the homosexual uncle had children of their own. Evolutionary biologists therefore argue that those members of society who do not have children themselves, but have no otherwise crippling conditions (a sign of ‘bad genes’!), can effectively raise the collective success rate of transmitting their collective pool of genes towards the next generation. In other words: small families, with just the parents and their children, have a much higher risk of not being able to bring up their children than large families, with grandmothers, unmarried aunts, homosexual uncles, transexual godmothers, and cousins with CAIS… which will have several available individuals to raise a group of children which will also pass part of their genetic material. While in the case of transexuality and homosexuality we still have no clue how exactly those ‘conditions’ are inherited (there seem to be no ‘transexual’ or ‘homosexual’ genes), with individuals with CAIS, it’s a different story: as said, the ‘bad’ AR gene is transmitted recessively via the maternal line. Many individuals with CAIS will even be able to lactate, and therefore serve as wet nurses, so there is evolutionary advantage of having them around to take care of the children when their genetic mother is not able to do so. This means that the ‘bad’ AR gene gets passed along — not directly, through one’s own children, but indirectly, through their nephews. And that makes the ‘bad’ AR gene be evolutionarily significant, which, in turn, explains why after hundreds of thousands of generations evolution has still not got rid of it — it serves an evolutionary purpose of raising the chances of survival of the species as a whole.

Tipping the balance: how easy it is!

What can we learn from this complex description of how people develop as male or female while inside the womb? What can we see that happens when things go wrong? What lessons are hidden behind these thousands of words?

First and foremost, every MtF transexual going through transition might wonder that actually it’s so easy to change their own bodies to become more feminine!

The lie-to-children is that if you remove androgens and add estrogens, your body will ‘naturally’ become more feminine. This sounds logical at the very basic, lie-to-children stage. But if you start to think a bit deeper than that, there surely must be something wrong with this reasoning, especially if we’re talking about an adult (i.e. post-puberty human) going through transition and doing hormone replacement therapy.

Remember, we have done most of our sexual development inside the womb — we get complete (even if not yet functional) genitalia, which are differentiated at the time of birth. While I’ve shown you some links about how so many parts of the human genitalia come from the same tissues, once they have been differentiated they are ‘fixed’, just like every other part of the body. You cannot change them by adding hormones: for instance, you can take the human growth hormone in your adult life to correct some conditions, but you will not grow taller or larger because of that! Why? Because the human growth hormone will act to make you ‘grow tall’ only at a specific period of time when the organism is developing according to a complex ‘blueprint’, which means that there is a special environment at a precise time in life where the human growth hormone is able to bind to the correct receptors which, in turn, will trigger genes that will add more cells and structures to the right places so that you ‘grow taller’. But once you have reached the end of your growth stage, the environment changes, those receptors will not bind any more to the human growth hormone, and thus they will not read those genes again. That stage of development is over; we have gone a few steps further in the ‘blueprint’, and there is no turning back. So, no, you cannot kickstart your growth process again by just adding the ‘right’ hormones, triggering the ‘right’ receptors, pushing the organism to start reading the ‘right’ genes again… it simply doesn’t work like that: once a specific stage is over, it is over, end of story. You can still administer human growth hormone to produce some effects — that’s why it’s used in certain therapies — and it will still bind to some other receptors (namely, it will increase production of all hormones), so there will be an ‘effect’. It just won’t be the effect of growing taller.

On the other hand… blocking androgen and administering estrogen no matter at what age will make your breasts grow. Well, of course how much they grow depends on your particular genetic makeup, but they will grow. And that’s not the only effect, of course — the skin gets softer; body fat gets distributed so that the coarse and angular shapes in the face will be replaced with softer and more rounded, feminine ones; hair on the scalp will become more luxurious, grow longer and healthier, and in some cases even bald men will regain hair growth; body fat will be channeled into the breasts and the hips and bottom; facial and body hair will become more sparse and much finer; muscle tone will disappear; the prostate gland will be reduced; etc. etc. etc. We all have read those descriptions millions of times; we all have heard transexuals describing it as ‘a second puberty’.

Actually, it’s even more than a ‘second puberty’: at puberty, what happens is that a mostly sexually undifferentiated individual (except for the genitalia and internal organs), under the effect of sexual hormones, will start to develop the secondary sexual characteristics appropriate to their gender, according to a ‘blueprint’. What happens with MtF HRT is that the previous ‘male blueprint’ gets cancelled (chemical castration), reversed, and a new blueprint, the ‘female blueprint’, is activated. And this happens in spite of age or degree of development of those secondary sexual characteristics!

You might now be wondering how this is possible! After all, I have started to describe how the ‘growth blueprint’ stops after a while, and no matter what hormones you take, you won’t start growing again. So why is the secondary sexual characteristics ‘blueprint’ still operational — in the sense that you can switch it off and on, even at an adult age — but other ‘blueprints’ are not? What makes this particular blueprint so different from others?

Remember what I told you about the unstable equilibrium that ‘defines’ what sexual characteristics blueprint is picked? Well, there is some logic for that. As you so well know, human beings have a certain ‘fertility age’, which in women begins with their menstruation and stops with menopause. Men are a bit luckier in the sense that their penises still work for quite some time, and that sperm production drops dramatically after ‘peak age’ (somewhere around 27 years) but since men produce gazillions of sperm cells, this drop of production will take a long, long time to have some effect. Nevertheless, it’s obviously not a coincidence that men’s peak sexual performance is at roughly the same time as women’s fertility stage.

Why doesn’t the female fertility stage last longer, i.e. like men, remain active until the end of life? This, again, is where evolution steps in. Bearing children places very tough demands on the mother; a lot of energy and resources have to be funneled towards gestating a new life in the womb, and, after birth, there is a lot of ‘used material’ that has to be replenished so that the womb can carry a new child again. This means further expenses of resources; not to mention the resources also needed for lactation to feed the newborn child. Because mortality rates for the human species was staggeringly high, it meant having the ability to bear, say, a dozen children, in the hope that at least two survived, possibly three (which would allow a population growth over the generations). So evolution had to find an equilibrium again — how many children ought a woman to be able to bear in order to at least sustain the population levels, given a certain (very high) mortality rate, while at the same time not depleting the resources of the female body until the mother dies from exhaustion way too soon to be useful for the society (namely, raising the children to adulthood)?

It is not a coincidence, therefore, that the period required for humans to reach sexual maturity is roughly the time that women are fertile, plus a margin; this means that, in theory, prehistoric human beings, who had a life expectancy of 40 years, would start to carry children by around 15, and continue to have, say, a dozen of them in the next dozen of years, while possibly raising some of the first children to adulthood. That would mean that mothers would at least have to live 30 years, with 15 years of fertility, assuming that the first children would survive. In practice, there is a bit of leeway — if out of a dozen children, the first eleven would die, and only the last one survived, then the mother would be 27 years old, be able to raise her last child to adulthood, and be 42 years old — about the age that humans would die from natural causes. During the raising of most of the children, especially the last ones, she should not be bearing any more children, but save her strength just for taking care of the living ones. To save resources, therefore, the organism ‘shuts down’ the ‘fertility’ blueprint. But there is more! Once she’s infertile again, she should show external signs of infertility, to make males aware that they should pick a different partner and leave her in peace. This is what the ‘menopause’ blueprint does: not only it shuts down the reproductive system, but it also affects the secondary sexual characteristics, making the woman ‘less sexually attractive’ to potential partners (the same, of course, also happens to a certain degree to males: as they age, and become less efficient in producing sperm, they will also lose muscle tone, become balder, their skin will wrinkle, etc. and so forth — also to give an outwards sign that they are not ‘healthy’ in terms of reproduction any more, but become ‘unattractive’ through the shutting down of the secondary male sexual characteristics ‘blueprint’). I don’t mean this as a form of disrespect, I’m just referring to the biological aspects of menopause; obviously the changes will be different from person to person.

And yes, I know all this sounds horrible — dehumanizing people, describing them as mere machines that are turned on and off according to the whims of Nature and evolutionary biology. Again, let me repeat once more, I’m definitely not using any judgement here, much less trying to discriminate and/or insult people who are aging (after all, I’m almost half a century old myself 🙂 — not exactly a youngling any more…). My whole point is to explain why the secondary sexual characteristics ‘blueprint’ needs to be switched on and off: it signals to the rest of the species when a person is in their fertile stage or in their infertile stage. And we need that in order to be able to pick the ‘right’ partners so that we can reproduce when both members of the couple are at their peak of their reproductive abilities, which raises the probability of success in terms of passing along their best genes to the next generation. It’s tough, but that’s what it means in terms of evolution.

Nowadays, of course, we have thrown evolution out of the window by not only artificially enhancing our average lifespan to more than twice its natural span, but also by artificially enhancing the success rate of children surviving after birth. Thanks to modern medicine, the actual rate of child deaths is infinitesimally small, compared to prehistoric (and pre-civilization!) levels, where possibly 50-80% of all children would never reach maturity. Today, in the European Union, an average of 99.6% of all births will at least reach 5 years of age.

The implications are staggering. This actually means that women can start their fertility stage much later, and that is seen by young couples marrying (and having children) much later in life than their parents and grandparents. In other words, it’s not unusual for young adults to enter their first marriage around 25-30 years of age — which would be close to the end of their natural lifespan in prehistoric times!

Ironically, these days, women start to menstruate earlier than before! But they delay their marriage for much, much longer; i.e. they might start menstruation at 9-11, and become sexually mature by 13, but they will only think of marriage after 25… contrast that to prehistoric women, who would probably only start menstruation by 15 and immediately become sexually mature, get a partner, and get pregnant.

This is an anomaly which comes from the fact that the menstruation cycle also has a ‘blueprint’ which says that it ought to start when the woman has reached a certain level where she is able to expend resources that will go towards the growth of new life inside her womb, as opposed to use up all those resources for her own growth, maturation, and survival. Because humans are so much better fed these days (and not only on developed countries: this is a trend that happens all over the world, even the poorest people in the poorest countries are much better fed than a hundred years ago, not to mention ten thousand years ago…), this means they have plenty of extra resources available much sooner in their lifetimes, and that’s what triggers their ‘fertility blueprint’ so much earlier. It’s another legacy of evolution. It’s no coincidence that sexual hormones are produced in the body using up cholesterol — yes, that same cholesterol that clogs up our arteries because of excessive fat intake. Since we have so many fatty products easily available, we have plenty of cholesterol, which in turn signals the body that it can safely start converting it to sexual hormones much sooner, and which, therefore, will trigger the fertility stage much sooner as well. And yes, this also explains a bit why more people are strangely more attractive these days than a few generations ago — attractiveness, as in ‘suitability as a partner’, is not only linked to good genes, but somehow also to being healthy and having a regular diet, as opposed to living near the starvation level. So, with more food available, we become prettier. I know it sounds stupid. But that’s how it is! It’s complex, and we’re artificially fiddling with evolution 🙂 by tricking our organism in soooo many different ways…